Dr Stephanie Hughes is a biochemist and for the past 20 years she has been working to better understand Batten disease. The disease is incredibly rare, affecting around six families in New Zealand, but it is the age at which it hits and the severity of the condition that has kept Dr Hughes invested for all these years.

Batten is a genetic disease which presents in children between the ages of 4 and 8 years old. The disease is associated with a build-up of proteins and waste products in the brain cells of these children. When these products build up they prevent cells from communicating with one another and eventually cause cell death. The children develop perfectly normally until the disease takes effect, and then they begin to progressively decline. They develop sleep disturbances, hallucinations, vision problems which eventually lead to blindness, seizures which increase in severity, cognitive decline similar to dementia, progressive loss of their motor skills, and around the ages of 6 to 12 the disease claims their lives.

There are at least 13 different genes which each cause some form of Batten disease, Dr Hughes and her team are focusing specifically on two forms which are known as CLN5 and CLN6. CLN5 is normally found in lysosomes, little pockets which digest proteins, fats, and other chemicals from the cell. CLN6 affects the membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum, which is responsible for the production of fats, proteins, hormones, as well as the detoxification of the cell.

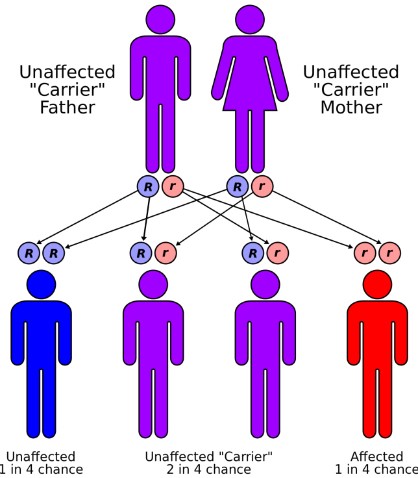

Most forms of Batten disease are hereditary and recessive, which means that both parents must be carrying the mutation but are unaffected by it. Unfortunately, this often means that by the time one child starts presenting with the symptoms of Batten disease the couple will have had other children, each of which has a chance of also developing the disease. Dr Hughes emphasised that the rarity of this disease means very little to those who are affected by it, “for the families of children with Batten disease it isn't rare at all,” she said, “they live with it every day”.

It is this reality, which sees previously healthy children dying and families suffering, which has driven her work. Dr Hughes is juggling as many projects as possible, trying to speed progress along. She and her team are trying to characterise the development of CLN5 and CLN6 so that future therapies can be accurately tested, they are examining the characteristics of viruses which could be used for gene therapies, and testing compounds which may be useful in alleviating seizures for some of the affected children. While there is a clear focus on finding a cure, Dr Hughes maintains her focus on treating those who currently need help. “As a researcher you need to have relationships with the parents so that you know the issues that they would like solved,” she said, “it could be trying to help the children to sleep better, so that the parents can sleep, or trying to find something that works for their type of seizures.” While looking to the future, she is still very much working to help those who are living with Batten disease right now.

When you are researching a disease which causes rapid degeneration and death in children, progress always feels too slow. “You're speaking with parents who needed a cure yesterday,” she said, “and you can't afford to give them false hope, because the truth is that we don't have the answers yet.” Progress, however, is always being made. “Twenty years ago we didn't know any of the associated genes, we didn't know about the proteins, we didn't know how a lot of the different types of Batten developed,” she stressed, “to go from that to having the genes, knowing many of the proteins, having hope for clinical trials, and having some clinical trials already starting: it's a huge amount of progress in twenty years.”

In theory, she believes, gene therapy should work for each version of Batten disease. “We just need to find the right way of delivering the right genes to the right cells that need to be treated,” she said, “and that sounds very straight forward but it is very difficult to do, [especially considering that] you need to do it early enough that the cells aren't gone yet.”

This year the Batten disease support and research association (BDSRA) conference, adopted the catch phrase 'Show Me A Cure!' a demand which would have been impossible to fulfil a decade ago. Thanks to the support of parents, funders including the BDSRA and Cure Kids New Zealand, and the efforts of researchers like Dr Hughes and her team that demand is much closer to being met.

If you've enjoyed this article, or any of the other work we do here, please consider donating to the Brain Health Research Centre. Your generosity could make a world of difference.