The Final Years

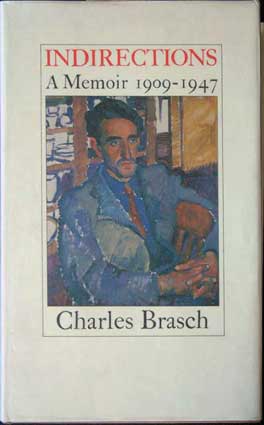

On 30 July 1952, Brasch wrote:'The excitement about my autobiographical sketches continues; details of the past keep swimming up into my mind, & I make notes of them. This is the kind of mood in which poetry comes, only this time it hasn't been poetry.' His 'Memoir' was first thought of about February 1947, and he began writing it soon after that. After working titles such as 'Finestra' or 'A Window', he finally settled on Indirections, which he finished typing on 14 October 1972. He never saw it in print. Abridged and prepared for publication by James Bertram, Brasch's schoolfellow at Waitaki, it finally appeared under the Oxford University Press imprint in 1980.

The publication of Joseph Malaby Dent's 'Everyman Library' began in 1906 and 152 titles were issued by the end of the first year. It was a very successful series which sold at affordable prices, i.e. one shilling a volume. The catch-cry:'Everyman, I will go with thee, and be thy guide, In thy most need to go by thy side' became familiar to many readers. On 2 January 1964, Brasch needed solace. Suffering from indigestion, a headache and a head cold, he grabbed this 'Dent' copy of Shakespeare's Sonnets and spent the afternoon 'reading wherever I could.'

William Shakespeare, Sonnets. London: Dent, 1934. Brasch PR2848.A1 1934

As long as Brasch could remember, there were regular Dante readings at his grandfather's house in Dunedin. Indeed, Dante's Divine Comedy was a book to which he often returned. New Year's Day of 1969 was a particularly busy reading day. During meals, Brasch read 'Frankfort & Newman & Hazlitt, with the TLS' and at night he read a poem by Alexander Blok. The day started well. Before breakfast, he read this edition of Dante, specifically Purgatorio XII.

Dante Alighieri, Purgatorio. London: Macmillan, 1952. Brasch PQ4315.3.BL16

Over the last ten years of his life, Brasch re-read old favourites, and continued to read newly published works. Some of those read included Mate (2 November 1966), Teilhard de Chardin's Letters (September 1967), the Aeneid (10 January 1968), poems by Adrien Henri, Brian Patten and Roger McGough (1972); and John Berger's G (October 1972). A further six are on display: Robert Graves's I Claudius ('read with horrid fascination' - 1964); Jean Genet's Our Lady of the Flowers ('a poetical work' - 4 November 1965); Patrick White's The Solid Mandala (March 1967); Alexander Solzhenitsyn's Cancer Ward ('quite ordinary' - 14 January 1970); C.K. Stead's Smith's Dream (5 November 1971); and George Herbert's Poems ('strong confident masculine phrasing' and 'a strength & fullness almost Elizabethan' - 11 October 1972).

Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Cancer Ward. London: Bodley Head, 1968. Brasch PG3488.O4 R31 A22;

Jean Genet, Our Lady of the Flowers. London: Anthony Blond, 1964. Brasch PQ2613.E53 N6 A23 1964

C. K. Stead, Smith's Dream. Auckland: Longman Paul, [1971]. Brasch PR9641.S7 S6

Patrick White, The Solid Mandala. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1966. Brasch PR9611.W5 S6

George Herbert, Poems. London: Oxford University Press, 1961. Brasch PR3507.A1 1961

Robert Graves, I Claudius. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin, 1953. Brasch PR6013.R35 I23 1953

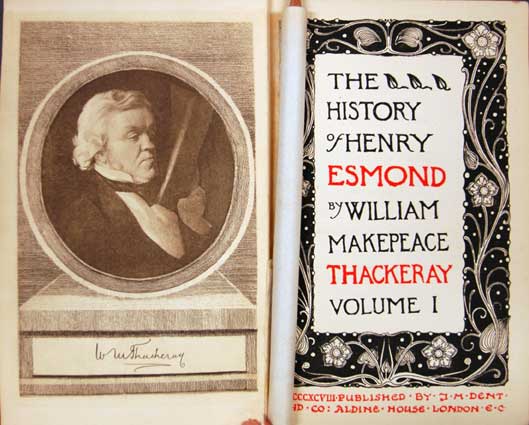

Brasch's last journal entries for 1973 (he died 20 May) detail on-going back-pain, growing weakness, the after-effects of drugs, and a desperate desire to finalise his Indirections. In those last few months, only a couple of books are mentioned. One was Thackeray's Henry Esmond, of which he writes:'Read Henry Esmond, but too fast, as a drug to take my mind off my pains.' It may have been this copy he read, which incidentally had belonged to his mother. She had received it as a prize for diligence in 1898.

William Makepeace Thackeray, The History of Henry Esmond. London: Dent, 1898. Brasch PR5612 1898

'Yes: I admire the author of Middlemarch, but I love the author of The Mill on the Floss.' So wrote Brasch on 3 November 1971 in response to George Eliot's The Mill on the Floss. He praised Eliot's 'view of life and her splendid depth of feeling.' The conditions in which he read the novel obviously helped. The railcar carriage which he was travelling in was almost empty, and there was good lighting. And then there was the scenery of the Canterbury Plains: 'Very beautiful western light across the level earth and through the trees; an often hard bare prosaic landscape where everything is flat shallow obvious - & now so lovely.'

George Eliot, The Mill on the Floss. Edinburgh: Blackwood, [1868?]. Brasch PR4664 1868

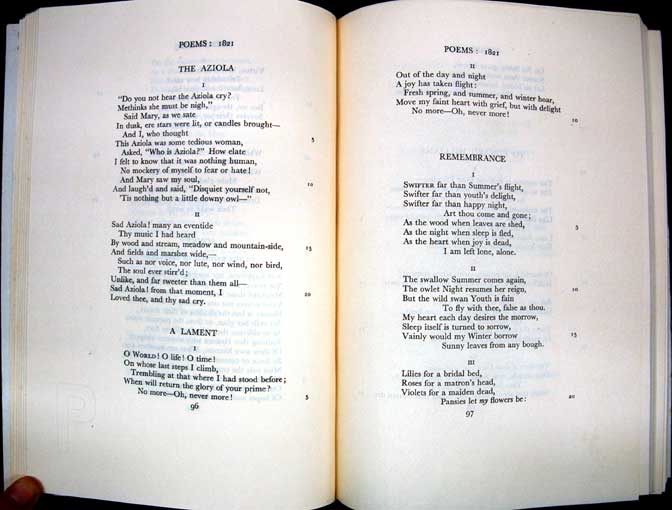

On 15 April 1969, Brasch read Shelley's 'O World O Life O Time' and on the one line 'Fresh spring, & summer, & winter hoar', he entered into a private discussion on scansion: 'Rossetti gives 'Fresh Spring, & Summer, Autumn, & Winter hoar'; Swinburne protested; Housman says Shelley wrote 'Fresh spring & Autumn, Summer & Winter hoar'… The ms shows that Shelley altered the line; in his fair copy (if it is that) he wrote 'Fresh spring & summer & winter hoar' leaving a gap thus. I agree with Swinburne that the standard reading of the line is very beautiful, but apparently Swinburne read it as having only 4 feet. I believe it must be read as having five, with a stress on 'fresh' &on 'spring'.' Brasch knew the poem well, admitting that 'I have loved the poem since I first read Shelley, & recited it to myself I suppose scores of times.'

Percy Bysshe Shelley, Poems. Vol. 4. London: Julian Editions, 1928. General PR5400 1926

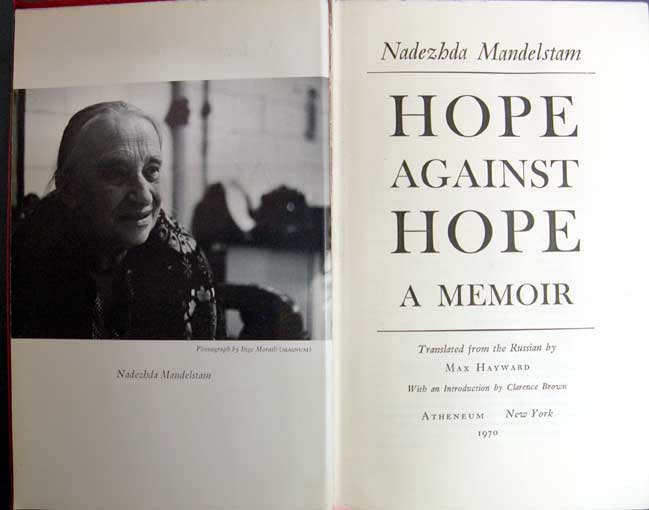

Osip Mandelstam is regarded as one of Russia's finest poets. He was arrested in 1934 for writing a few satirical lines on Stalin and died in a Gulag in 1938. His wife, Nadezhda Mandelstam (1899-1980), spent much of her life heroically preserving his poetic heritage. During September 1972, Brasch read her memoir Hope against Hope (1970)to Ted Middleton. Brasch was impressed with her: 'She does not write about herself, but one lives through her book with her almost more than with M – she must have been fully his equal, a very great woman indeed.' It may also have been the last big book Brasch read. It was certainly appreciated: 'It is good to be reading the book so slowly; it sinks in, and is with me now all the time.'