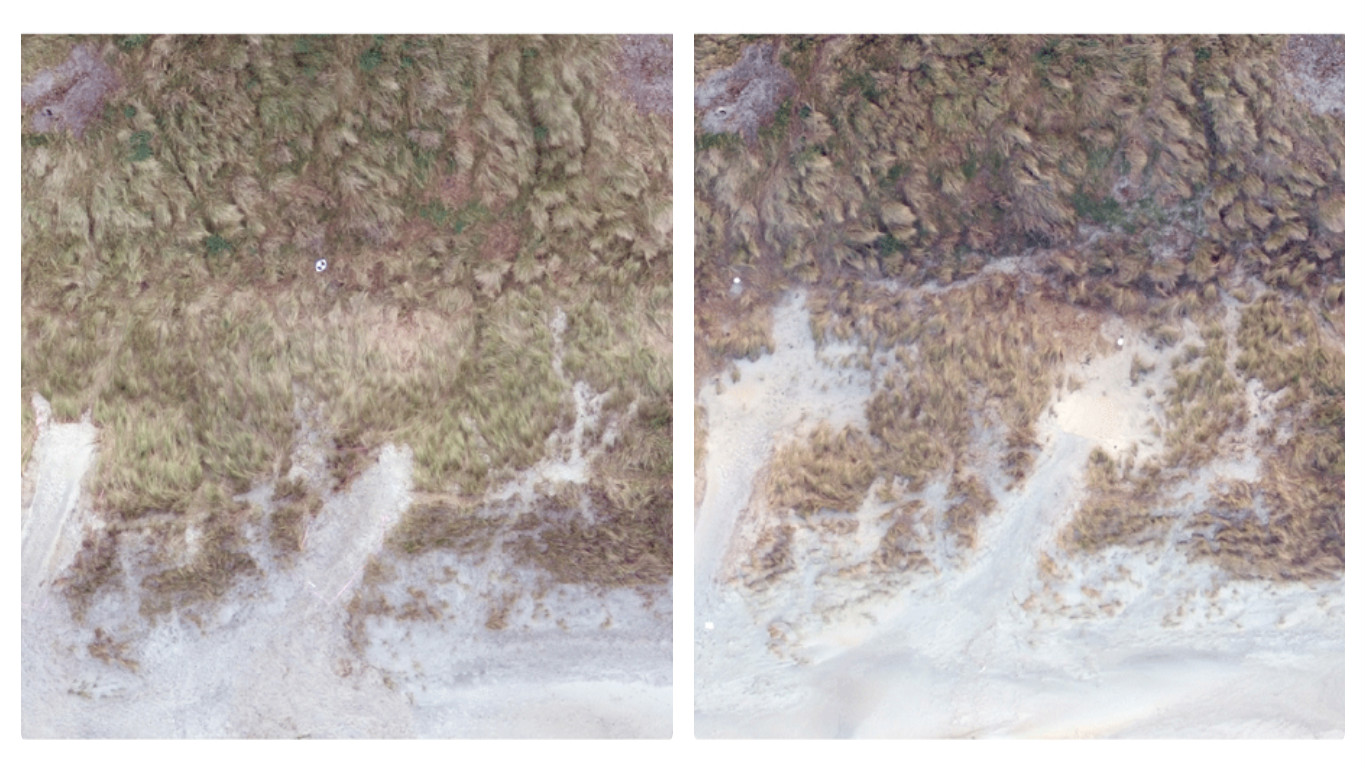

At St Kilda ... (from left) A drone image of the dunes shortly after the gaps were carved, and sand build-up behind the face of the dunes.

Experimental work to improve the resilience of vulnerable sand dunes at South Dunedin's St Kilda Beach fulfils Otago Geography Master's student Tom Simons-Smith's desire for his research to directly benefit people.

Passersby will notice three notches of varied dimensions dug at a slight angle into the St Kilda Beach foredune (closest to the water). They are sizeable – the biggest notch took a large digger nearly two hours to complete, the smallest 40 minutes.

Rather than locals being upset, Mr Simons-Smith says they are uniformly supportive when they hear his research aims to encourage sand movement inland to create a wider and less peaked foredune, which will better protect neighbouring John Wilson Ocean Drive from storm waves.

He believes the locals' reaction reflects public concern about rising sea levels and low-lying South Dunedin being inundated.

“These notches create localised increases in wind speed, as well as steering winds onshore.”

Ms Simons-Smith is hoping the change will encourage sand to be deposited in the swale (small valley) between the foredune and the bank in front of John Wilson Ocean Drive.

"Many of us have been raised to avoid walking on dunes and disturbing the plant cover. In this case, a little disturbance may create a more durable foredune."

“This would make the dune broader and more rounded, which may then reduce the risk of severe dune damage in storms. It may also help people access the beach.”

“We're collecting detailed data on how wind flow and sediment movement differs between three notches of different depths and widths so the optimal shape can be used in future.”

“It may be you don't need notches as large as these. Perhaps just cutting paths in the marram grass may have the desired effect."

“Many of us have been raised to avoid walking on dunes and disturbing the plant cover. In this case, a little disturbance may create a more durable foredune.”

“This work is experimental, but if I can learn which notch morphology or shape is most suitable in this area, maybe we can do something like this on the entire coastline, which could delay — perhaps for years — the need to protect John Wilson (Ocean) Drive with a seawall or similar structure, or to shift John Wilson (Ocean) Drive inland.”

Mr Simons-Smith, who is based in the University of Otago Department of Geography, expects to hand in his thesis by early next year.

Its content will be enhanced by his collaboration with fellow Master of Science (Geography) student Julia Moloney.

Early on still mornings, you can find Ms Moloney flying a drone above St Kilda's dunes, gathering data for her own investigations into using drones for coastal research, testing her data against current dune surveying methods.

She says that Mr Simons-Smith's experiment gives her “an opportunity to see how successfully we can use low-cost drones to measure changes in elevation, and volume changes in the dunes.”

"Tom uses the vertical photos taken by the drone. You can see a lot more from a birds' eye perspective."

“I process the images and create digital surface models, and Tom uses the vertical photos taken by the drone. You can see a lot more from a birds' eye perspective.”

The supervisor of both students, Geography Assistant Professor Mike Hilton, says there was no foredune before European settlement. The current dune profile developed after the construction of John Wilson Ocean Drive, which is New Zealand's only true dyke, built in the 1950s to keep the sea out of South Dunedin.

“Then exotic marram grass was introduced to stabilise the dune. But marram thrives on the back of dunes and slowly pushes them toward the sea, which makes the dune vulnerable to wave erosion. If Tom's research does work, we'd have a coastal management outcome.”