Vision fulfilled

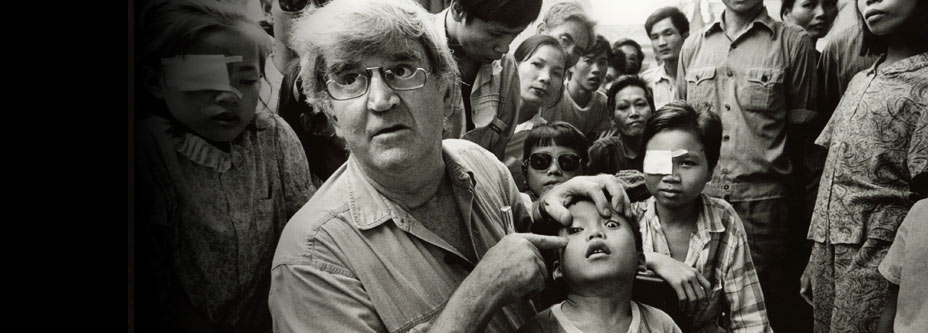

From a working-class Christian Socialist background, Otago alumnus Fred Hollows developed a social conscience early in life. This never left him as he worked to save the eyesight of tens of thousands of people in the developing world. Since his death in 1993, the Fred Hollows Foundation has continued his mission.

Fred Hollows is more of a household name in Australia than in New Zealand. Among many honours heaped upon him across the Tasman, his face appears on a special edition Australian coin and, in 1990, he was voted Australian of the Year.

It's not a bad record for a lad born in Dunedin and educated at the University of Otago.

His life's work of restoring sight to poorer peoples is the stuff of legend and, since his death from cancer in 1993, his influence has increased dramatically. When he knew his time was limited, his colleagues set up the Fred Hollows Foundation to carry on what he started and to expand its horizons long after he was gone.

Two decades later, Gabi, his widow and co-founding director, says even he would have been amazed at his legacy. The Australian and New Zealand arms of the Foundation are active in 30 countries across Asia, Africa, Australia and the Pacific.

They have treated almost a million people for eye problems, established revolutionary lens manufacturing businesses, and set up eye clinics and teaching institutions that are well advanced in training local medical professionals to be able to continue Hollows' work.

The Australian Foundation set up six-month fellowships for recently-graduated ophthalmologists, giving them invaluable experience working in low-resource countries while they share developed world experience and help with clinics.

Australian fellows have regularly spent two months of their term working with the New Zealand Foundation in islands around the Pacific. The first Kiwi recipient of the fellowship was Otago graduate Dr Jesse Gale (see below). Now the New Zealand office is launching its own one-year fellowship, based at the Pacific Eye Institute in Fiji and serving the Pacific Islands.

For New Zealand Foundation Executive Director Andrew Bell – another Otago graduate – the new fellowship is part of a natural expansion of Hollows' original vision.

“Fred's idea from the very start was not just to give people back their sight where he could, but to put in place local schemes that would enable people in low-resource countries to look after their own.

- Andrew Bell, Executive Director, Fred Hollows Foundation NZ. (Photo: Michael Bradley)

“Young ophthalmologists spending time in these often remote locations can continue Fred's work, pass on their knowledge and also learn new ways of doing things from the local eye-care team.”

Everyone wins. Each positive combination of developed and developing worlds goes a small way to reducing the imbalances of opportunity that Hollows sought to address.

It has taken decades for Hollows' quest for social equality to gain the momentum that it now has. His own social awareness had its roots in New Zealand – and the University of Otago played no small part in its development.

Until Hollows was seven he was raised in Dunedin, which he remembered as a cold, hard place in the 1930s. The family followed his father's railway job to Palmerston North, but later Fred returned to Otago to study religion and the arts.

As a regular church-goer from a non-drinking Christian Socialist family, he thought he might be on track to join the ministry, but Otago opened his eyes to new experiences.

As time passed, he seemed more at home in the pub with a few of the lads and, after a summer job at a mental hospital in Porirua, he returned to Otago a changed character. He continued his arts degree, but dropped divinity for chemistry and physiology, doing so well in later years that Otago offered him a place to study medicine.

He wasn't a model med student. He confessed to studying hard in bursts, but playing up a bit, and spent a lot of time in the mountains.

“Mountain climbing got into my blood then and it was important to me for the next 30 years,” he later said. “It puts things into perspective – risks and skills, life and death, gives you the measure of problems and people.”

Hollows no doubt measured his fellow medical students, many of whom were from wealthy backgrounds. He said he observed them, but didn't aspire to join them. His social conscience was already formed.

In 1965 Hollows moved to Australia, where he visited many Aboriginal communities. He was shocked by the poor standards of eye health, particularly the incidence of trachoma, one of the world's leading causes of blindness. It's an infectious disease associated with poverty and overcrowding and a lack of access to clean water and sanitation.

Hollows made it his mission to address the imbalance between medical services in the cities and the outback. Between 1976 and 1978 he and his team visited 465 indigenous communities. They screened 100,000 people for eye disease, treated 27,000 cases of trachoma and performed 1,000 eye operations.

He also helped establish the first Aboriginal-run medical centre, realising that the key to the future was not just to offer help from the outside, but also to train the locals to help themselves.

In the 1980s he worked with the World Health Organization in developing countries across Asia. He was appalled at the lack of medical resources and the prevalence of avoidable blindness.

Wubujub, a 12-year-old boy who has had a cataract for around nine years, waits to have his bandages removed in Daru, Papua New Guinea. (Photo: Hugh Rutherford)

Along with like-minded locals, Hollows adopted new techniques for performing basic cataract operations, and began setting up laboratories in Nepal and Eritrea to manufacture inexpensive plastic lenses to restore sight at a fraction of the cost incurred in the developed world.

Today those businesses produce millions of lenses, with some of the proceeds reinvested in training local eye doctors and nurses.

In the last year of his life, Hollows began planning the Foundation that has continued his crusade to end unnecessary blindness in developing countries.

In New Zealand, Andrew Bell is in his third year with the Foundation. In his native South Africa he had worked with urban and rural poor and was heavily involved with social change.

He came to New Zealand with the intention of continuing postgraduate work started in South Africa, later becoming involved in the important areas of international aid and development work with the Presbyterian Church.

It was only after meeting Professor Murray Rae, head of Otago's Department of Theology and Religion, that he found a way to complete his Master of Ministry while still working full-time. Otago was receptive to transferring the credits of Bell's existing work and supportive of his efforts, he says.

"Otago was very welcoming to the distance learner. They understand that you are in the cut and thrust of daily work and make it as easy as possible to do the studies.”

After graduating, Bell moved to the Foundation, ready to capitalise on its key difference from many international organisations.

“Unlike many big organisations that provide broad areas of service in multiple countries, we do one thing and we do it exceptionally well. We currently provide some 50 per cent of eye care in the Pacific.”

Before taking the director's chair, Bell saw the completion of the Pacific Eye Institute in Fiji, the National Eye Centre in Timor-Leste and the eye clinic at Kimbe General Hospital, Papua New Guinea.

“Over the last 20 years there have been huge advances made in ophthalmology. Lenses used in cataract operations have gone high tech, and laser equipment and new medications are available.

“The science of eye care has developed tremendously since Fred's death. But, although surgical techniques have developed, small incision cataract surgery is still the preferred intervention in the developing world.”

Bell says Hollows is still the DNA of the Foundation and the inspiration for its work. Its methods may have changed and its scope expanded, but its basic goal of eliminating avoidable blindness in the developing world has not changed.

Hollows may have been dead for 20 years, but it seems his vision is as sharp as ever.

Dr Jesse Gale examines the eyes of a patient during a surgical outreach in Tonga. Photo: James Ensing-Trussell

New insights

Dr Jesse Gale would prefer not to be a public face of the Fred Hollows Foundation.

Dr Jesse Gale examines the eyes of a patient during a surgical outreach in Tonga. (Photo: James Ensing-Trussell)

But, after six months working to restore sight in Nepal, Alice Springs and around the Pacific, he's prepared to commit to most things if it means supporting fundraising for the Foundation.

“It's not so much a charity organisation as a development organisation. It has such a long-term goal and that is an important point of difference. It's really worthy of all those $25 donations. It's money well-invested.”

Gale has seen where the money goes. He's seen the excitement and gratitude of patients when the bandages come off and they can see for the first time in years.

He's seen the future return to people who thought they had none and he's seen a world where acceptance of loss of sight is the norm, even though it can be treated easily and inexpensively.

He's also learned techniques and skills that are rarely seen in mainstream eye care.

“I haven't finished my training. There's still a lot to learn and the Foundation job was a great opportunity to learn more.

“It's a great privilege to be able to travel so widely and be able to learn from lots of different people. You quickly find you are not there to fix the problem – local doctors are often doing that on their own – but you are there to see new ways of doing things.

“I was being trained, not just to become a better doctor, but to have the skill-set to train other doctors in the future. The Foundation's goal is not just to address current needs, but to create long-term strategies.”

Gale started medicine at Otago not really knowing what he was in for, but found his niche in clinical ophthalmology. “It's scientifically fascinating and you get job satisfaction from improving someone's life. You also don't face the tragic side of medicine – my patients aren't in danger of dying.”

The Foundation has given him new insights. “You do new operations and find out about diseases not common in New Zealand, and about matching the health service to the needs of the population.”

Learning went both ways and Gale was able to pass on some of his knowledge at the new Pacific Eye Institute in Suva, where some trainees would become the first eye doctors in their home countries.

Gale is now in Los Angeles – “a planet apart from where I've been” – studying neuro-ophthalmology, with plans to study glaucoma at Cambridge before returning home to New Zealand.

“I'm not sure what shape my contribution will take, but my long-term plan includes going back to some of the poorer countries.”