Monday 3 February 2014 2:30pm

Monday 3 February 2014 2:30pmMicrobiologist Professor Greg Cook has been awarded the University of Otago's 2014 Distinguished Research Medal for ground-breaking work that may lead to a breakthough in the fight against diseases such as tuberculosis. He is also committed to mentoring a new generation of talented researchers.

Dr Chris Greening and Professor Greg Cook

When Professor Greg Cook accepted the University of Otago's most prestigious research award, the Distinguished Research Medal, he was quick to credit his team for their contribution to the honour. The medal is the latest in a long list of accolades for work done by Cook's laboratory within the Department of Microbiology and Immunology.

“The award for what we have been doing may be to an individual,” says Cook, “but it's the result of a team effort over many years.” He says current breakthroughs are the culmination of a significant contribution from many people over time, as well as the collegial environment at the department.

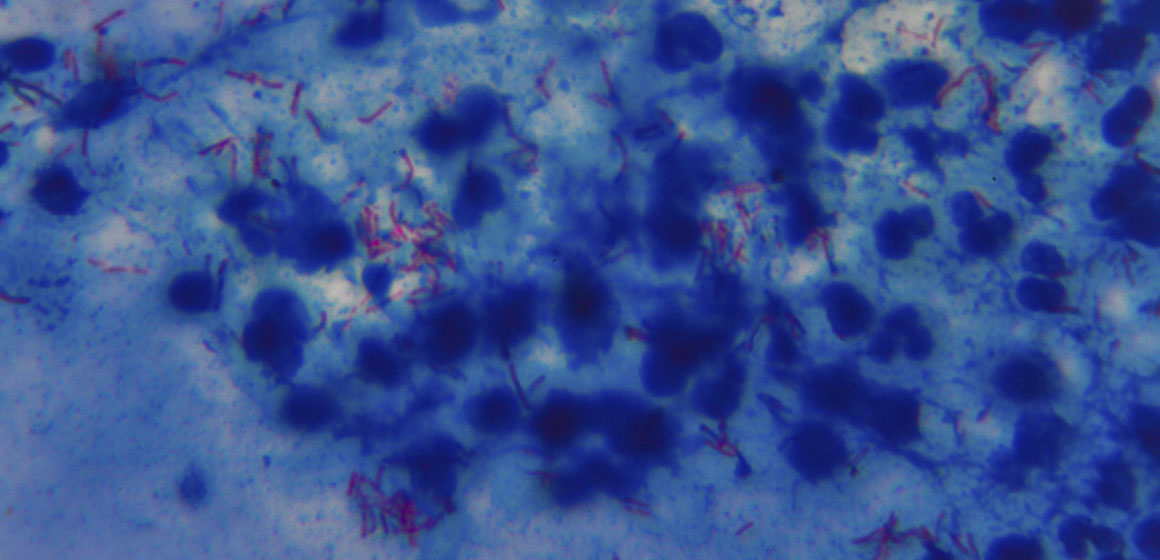

Cook and his colleagues are at the forefront of research into the physiology of bacteria, particularly those that can survive in extreme environments. Their most recent discoveries may lead to developing new drugs to target global health threats such as tuberculosis (TB).

A third of the world's population is under threat from TB, partly because it has become resistant to current drugs. Cook believes they are close to being able to close down the disease-carrying microbes' survival mechanism, which could prevent the spread of TB.

“Our research is focused on trying to understand how human pathogens like Mycobacterium tuberculosis metabolise and grow in our bodies. If we can cripple this ability to metabolise, we are confident we can develop new strategies to treat TB patients.”

They have recently discovered how mycobacteria can survive long periods with little or no oxygen – an understanding that is vital to eradicating the large human reservoir of latent TB, that can come to life when conditions are favourable.

Significantly, they have found that the bacterium can switch its cellular metabolism from a primarily oxygen-based one, to one that uses fermentation for energy production instead, metabolising molecular hydrogen until it can source sufficient oxygen to grow again.

Just as Cook received mentorship from his early professors, he is now nurturing younger researchers who are a vital part of his team and potential academic stars of the future.

“One of the most enjoyable parts of my job is the time I spend with my postgraduate student family and seeing these students graduate and go on to have their own scientific careers and families.”

Among a line up of feted international collaborators on a rush of academic papers in 2014 are some of Cook's research students. The latest PhD student to graduate from his laboratory, Dr Chris Greening, recently led the ground-breaking study on the role of hydrogen in the persistence of mycobacteria and how this hydrogen energy system works.

Greening, a first-class graduate at the University of Oxford, had been completing his honours research project in Professor Stuart Ferguson's laboratory when his supervisor invited Cook to Oxford to speak on his work with extremophiles.

“I was blown away by the type of research he was doing,” says Greening. “He was one of those people who would ask the big questions and had ingenious ways of answering them.”

Greening wrote to Cook to ask if he would take him on for a PhD. “I had a very enthusiastic response, saying the type of research I was doing would be perfect for his lab. He could tell that I was genuinely interested in bioenergetics – the study of how organisms make their energy. It helped that my honours supervisor literally wrote the book on the subject.

“It was a leap of faith on Greg's part to take me on on the strength of a few email chats. He was very helpful with the process of getting me out here as an international student and even met me at the airport.”

Cook trusts his instincts. “I always go for personality. Some might consider this a weakness, but if you get on well with someone, you should be able to do great stuff together and have some fun. The academic record is relevant, but you have to work together too. If you get both, fantastic.

“One of the most enjoyable parts of my job is the time I spend with my postgraduate student family and seeing these students graduate and go on to have their own scientific careers and families.”

“Chris was academically very strong, but still a little green in the experimental lab. But I trusted him to come through.”

He has. In the last six months alone, he and Cook have published six papers together, two of them in one of the world's top scientific journals, the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Under Cook's supervision, Greening took ownership of the project and drove it to publication, ensuring that every experiment was targeted towards addressing a hypothesis and developing a story – teasing out how mycobacteria regulate and use their hydrogen energy systems for persistence. Greening has shown that interfering with hydrogen cycling in Mycobacterium smegmatis can reduce the microbe's survival rates a hundredfold.

Now Cook hopes that they can use their knowledge to disturb the survival process in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. “The key thing we have to do now is to translate our findings into a new drug for TB. We're on the verge of doing that with our latest compounds, but it's still a little way off.”

Greening credits his success to an encouraging family, a grounding of rigorous tutorials at Oxford and, most recently, to Cook's mentoring. Having an open and supportive mentor for this study was crucial to him. “I regularly discussed my ideas and findings with Greg, usually in an informal setting. He motivated me with his enthusiasm for the project and helped me to stay on target and to translate theory into practice.”

Cook says his approach is straightforward. “I believe in empowering people to get the best out of them. Control them and nothing happens. They don't grow and you don't leave a legacy behind you. I've trained more than 50 postgraduate students and each has excelled in one way or another.

“A key factor in Chris's success was his ability to stay engaged with his project throughout the course of his PhD. This requires dedication. Chris was always thinking and planning his next paper. His ability to assimilate and remember scientific literature was second to none. He always asked the right questions, whether on his own project or that of another lab member.”

Greening is taking Cook's advice and heading overseas for international experience, but he will continue to work with the team in Dunedin on the survival mechanisms of mycobacteria.

“It's really pleasing to see how Chris has come through,” says Cook. “I won't be surprised if he turns out to be one of the best postgraduate students I've had and that this department has ever graduated.”

Funding

- Marsden Fund

- Health Research Council Explorer Grant