The first child conceived using a controversial fertility technique was recently revealed to have been born. The technique, known as mitochondrial-replacement therapy, saved this child from developing a rare genetic disease called Leigh syndrome which he would have inherited from his mother.

Leigh syndrome is a childhood-onset neurodegenerative disease. In most cases the symptoms begin when the child is around a year old starting with trouble swallowing, diarrhea, and vomiting. Lactate builds up the child's blood, their urine, and in the fluid which cushions their brain causing these fluids to become acidic. Muscle fibres are broken down, and lesions form on the brain. These children begin to have seizures, eventually lose their sight and muscle tone, and also experience painful muscle spasms. Most do not survive past the age of three.

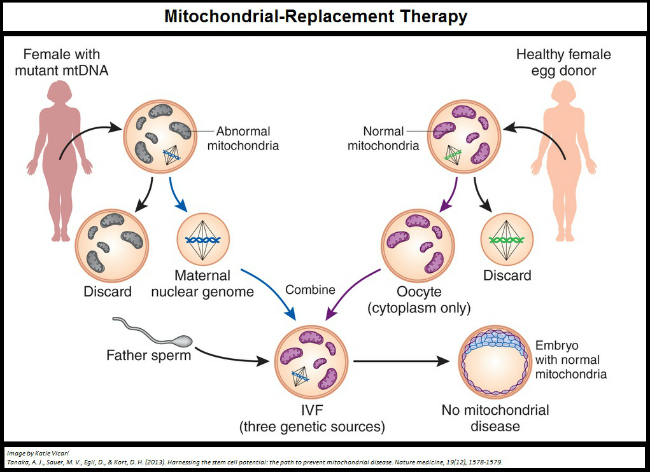

It is no wonder then that the parents of this now five month old baby wanted to ensure he would not inherit Leigh syndrome. In most situations with an inherited disorder like this an egg donor would have been necessary, which would entirely erase the mothers genetic input. In this case, however, the disorder was not inherited from the nuclear genes she would pass on her son but from the DNA in the energy supplier within her eggs: her mitochondria.

Mitochondria are pieces of cellular machinery which make most of the energy your cells need to survive. They have their own genes and they divide, like whole cells, to make more of themselves. Mitochondria from sperm are destroyed after fertilization, so through every generation mitochondria are passed from mother to child. Your mitochondria are identical, or almost identical, to those of your mother and her mother and her mother's mother and so on. However, over time changes to the DNA of mitochondria can occur and some of these changes can be detrimental or even fatal.

It is unclear whether the mother of this child has a very mild form of the syndrome, or if the mutation which causes Leigh syndrome is only impacting the mitochondria in her eggs; what we do know is that the mitochondria she was going to pass on to her baby would have eventually killed him. Instead her DNA was transferred to an egg cell with healthy mitochondria, and her son now stands a much better chance of having a normal, healthy, and full life.

Since this child's existence was revealed reports of other children, one now born and two others conceived, have come out. These later three babies are not believed to have been conceived to avoid mitochondrial diseases, but to bypass fertility problems being caused by the mother's mitochondria which had stopped previous pregnancies from developing.

As the number of children born rises so too does concern surrounding the procedure. We simply do not know how this kind of treatment will impact development. There is particular concern about how these children might age, and whether the mismatch of their DNA and mitochondria might put stress on their cells or cause mitochondrial failure later in life. Failures of mitochondria have been linked to a number of neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease, and while that risk may be worth taking to avoid mitochondrial disease it is not one to be ignored.

There is also uncertainty about whether these children will truly be free of their mitochondrial disorders, or whether the initial replacement therapy will just slow the progress of the disorder. Mitochondria don't act like the rest of our cells, they divide on their own and they appear to be able to compete with one another for resources. A small percentage of diseased mitochondria are unavoidably transferred along with the maternal DNA into the donor egg, and there is no guarantee that these diseased mitochondria won't eventually take over.

All eyes are on the researchers and doctors who helped create these children, but it may be decades still before we know if they did the right thing.

If you've enjoyed this article, or any of the other work we do here, please consider donating to the Brain Health Research Centre. Your generosity could make a world of difference.