As part of Brain Week Associate Professor Phil Sheard, who recently won the Otago School of Medical Sciences lecturing award, gave a talk about how muscles weaken with age. While this process is, to some extent, an inevitability he explained that exercise could improve our strength as we age.

In general it is believed that we lose about 1-2% of our muscle mass from the age of 50 onward, but weakness of muscle may start even earlier than that. Even top athletes struggle to remain competitive above the age of 35, despite decades of training and practice behind them. Loss of power from our muscles is inevitable, even for the fittest and strongest of us, but the rate and intensity of this loss may still be under our control to some extent.

Associate Professor Phil Sheard explains how this weakness happens. He says it is due to two independent processes: muscle fibre atrophy (shrinkage), and muscle fibre death.

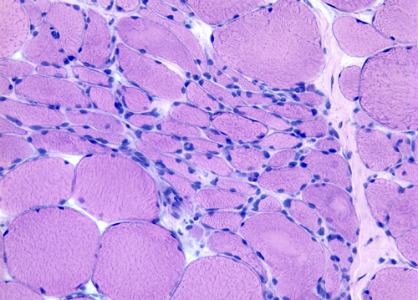

When an animal is young the muscle fibres which make up its muscles are consistent in size, but as it ages some of these fibres will shrink. The thinner the fibre is the less force it generates when it is activated. Why do some fibres shrink while others stay the same? Because they lose their connection with the nerves which activate them. In the image below the atrophied fibres in the centre of the image have lost this connection.

Our muscles are activated by nerves which arise in the spinal cord. If a muscle fibre loses its connection with a nerve then it receives no activation signals and so will not contract with the rest of the muscle. Muscle fibres that are not being used gradually will shrink, as anyone who has had a limb in plaster will attest.

Our muscles are activated by nerves which arise in the spinal cord. If a muscle fibre loses its connection with a nerve then it receives no activation signals and so will not contract with the rest of the muscle. Muscle fibres that are not being used gradually will shrink, as anyone who has had a limb in plaster will attest.

In a healthy muscle every fibre is connected to a nerve, so why do some muscle fibres lose this connection as we age? Assoc Prof Sheard says it is due at least partly to a chemical called Rapsyn. Under normal circumstances this chemical exists in a high concentration in the neuromuscular junction, the area where the nerve connects to the muscle fibre. However, rapsyn levels drop as we get older and this correlates with nerves becoming disconnected from their muscle fibres.

Is there anything we can do to stop this? Yes. Associate Professor Sheard explained that rapsyn levels have been shown to increase after exercise. This results in nerves sprouting and reconnecting with their muscle fibres, and prevents other nerves from disconnecting from their muscle fibres. Exercise, therefore, should be able to preserve muscle strength and reverse muscle loss associated with atrophy.

But this is only one piece of the puzzle. What about muscle fibre death? Associate Professor Sheard explained that the death of a muscle fibre is not related to atrophy, and in fact the muscle fibres which die are still connected to their nerves. Instead, dying fibres develop tiny holes in their membranes, which lead to a failure and eventual death of the fibre.

While some muscle fibres will die as we age, the number of them which are impacted by this diseased process is also reduced by exercise. Associate Professor Sheard says that it is a kind of 'use it or lose it' scenario. Our bodies won't put the energy into maintaining functions we don't use anymore, so the less we exercise the less we can exercise.

We will all grow weaker as we age, but we don't have to passively accept it. Keeping active, and giving our muscles something to work for may be the key to remaining mobile for longer. It is never too late to start, never too late to get back some of the strength that has been lost. If we give our muscles a reason to exist then they will stay with us.

If you've enjoyed this article, or any of the other work we do here, please consider donating to the Brain Health Research Centre. Your generosity could make a world of difference.