How do we attribute value to our goals? Does an increase in difficulty somehow motivate us more? And when is our motivation the greatest? These are the questions which have guided PhD student Thom Elston throughout his research process. Thom wanted to understand motivation at its base level and see what exactly it is that drives goal-oriented behaviour.

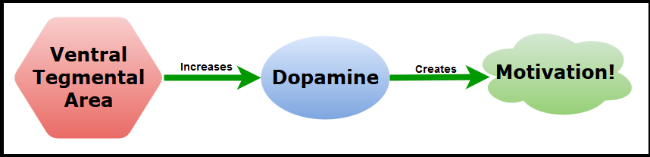

He did this by recording the activity of the ventral tegmental area in the brains of rats. The ventral tegmental area is an area of the brain which releases a chemical called dopamine, which is thought to represent reward in the brain. It's your brain's way of saying “That was good, let's do it again!” We usually hear about reward systems being hijacked by addiction, with high levels of dopamine being release in response to illicit substances or dangerous activities, but even something as simple as tying your shoes can cause a dopamine release. It's all about the amount released.

Previous research showed that the amount of dopamine ramps up as a rat gets closer to its goal. If the rat stops then the dopamine stops, and even if one rat takes twice as long as another the same amount of dopamine is released. This tells us that the goal is worth a certain concentration of dopamine, and the increases in concentration as the rat gets closer to its goal is like the brain saying “Yes! You're on the right track! Keep going!”

Thom wanted to know if the activity of the ventral tegmental area, a source of dopamine, would increase or decrease relative to the amount of effort the rat believed it would take to acquire a fixed goal (3 cocopops). What would happen if the rat found out that its goal was more difficult or easier to attain than expected? When the rat realized the goal was more difficult to attain, would the dopamine concentration drop or would the reward-related activity of VTA be higher than normal?

In order to test this Thom set up a simple track for the rats to run through. At the end of the track the rat received a food reward (3 cocopops) and, as expected, activity in the VTA hit its peak.

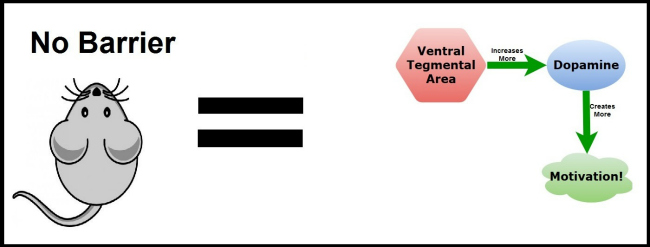

For the first stage of the experiment, the rats ran the track without any barriers, and their VTA activity increased consistently as they got closer to the end.

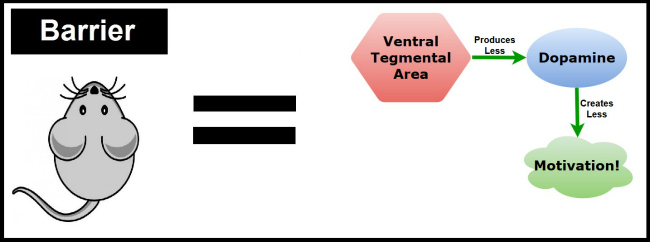

In the second stage of the experiment, Thom switched things up a bit. In 50% of the trials the rats ran through the normal track, but in the other 50% of trials Thom introduced a barrier which they had to climb over. The rats were signalled whether the present trial was a “flat” trial or a “barrier” trial, which enabled Thom to track how the rat's estimation of future value changed over time. Thom found that VTA activity dropped when the rats anticipated the barrier, and jumped up if they anticipated no barrier. However, by the time the rat got to the end of the track, whether there was a barrier or not, VTA activity was the same.

This showed that the rats had a moment-by-moment valuation of their goal – they were constantly weighing up the reward vs the effort required: As the rats approached the goal, their brains were saying “Yes! This is good! We'll be there soon!” but when the rat knew a barrier would be in its way, it's as though their brain has revaluated the situation. “It's not great,” you could imagine them saying, “but we might as well go through with it.”

Thom's work suggests that behaviors themselves can be rewarding or punishing and that the brain combines both cost (effort) and benefit (reward) in the VTA. This shows us that the brain constantly updates the value of a future goal, depending on what we have to do get it. The result of this cost-benefit analysis may indicate how motivated we are to pursue a future goal.

Research like Thom's helps us to understand why it is we do what we do. If we can understand why we choose some routes instead of others we can start to look for ways to change those patterns, ways to alter our motivations.

Our sincere thanks go out to Thom Elston for sharing his work at the BHRC 2016 Conference, and we look forward to seeing where his research takes him next.

If you've enjoyed this article, or any of the other work we do here, please consider donating to the Brain Health Research Centre. Your generosity could make a world of difference.