Monday 3 February 2014 9:25am

Monday 3 February 2014 9:25amAmerican actor and humanitarian Angelina Jolie drew worldwide attention to the familial risk of breast and ovarian cancer. Otago's Dr Logan Walker is now working to develop genetic screening tools to identify those most at risk of these cancers, enabling them to make informed decisions.

“If you take 100 New Zealand women, 10 of them will likely develop breast cancer. If you take 100 women with a mutation in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene, up to 80 will develop breast cancer. Compare this with environmental factors such as obesity or drinking alcohol, which might increase the numbers of women developing breast cancer to something like 12 or 13 women out of 100. You can see what a massive role genetics play.”

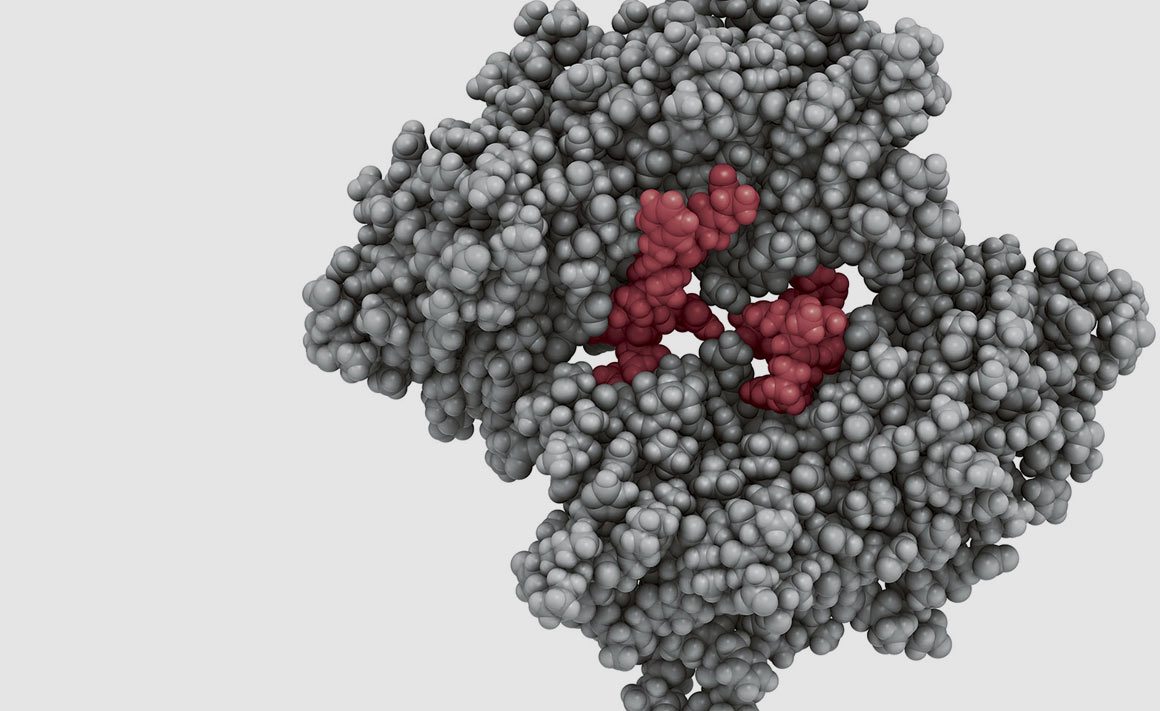

Understanding the role of genetic changes, or mutations, to breast and ovarian cancer risk is the focus of Dr Logan Walker, from the University of Otago, Christchurch. His ultimate aim is to develop genetic screening tools that identify those most vulnerable to getting cancer so they can make informed decisions about treatment options.

One of these options, brought to public attention by movie star Angelina Jolie, is surgery to remove breasts and ovaries.

“Angelina Jolie had a mutation in the BRCA1 gene and she took people on her journey and decision to have surgery to reduce her risk. Surgical intervention can reduce the risk from over 80 per cent likelihood to less than five per cent. The BRCA genes are really, really important because they repair other genes and maintain the integrity of our cells. Everyone has these genes but some people inherit a mutation, which is what gives rise to a far greater risk,” Walker explains.

As leader of the New Zealand Familial Breast Cancer Study, he and his colleagues study women like Angelina Jolie who have a strong family history of disease.

Walker says the increasing affordability of genetic screening technology over the past decade has revolutionised the testing of high-risk breast and ovarian cancer patients.

“At the turn of the century it cost $100 million to screen the whole genome. This year you can get it done for less than $2,000. As costs go down, a lot more people will have their DNA screened in this manner."

"While it is exciting, this access to genetic information is going to put a lot of pressure on health professionals because they have to know how to interpret that data and what to do with it.”

Genetic testing results are already providing difficult scenarios for clinicians, genetic counsellors and patients.

“Sometimes your family history might suggest you are at high risk, but no known genetic changes are obvious. In other scenarios, genetic testing might show a genetic variation, but we do not know if it is associated with an increased risk of cancer. These unresolved screens put patients in limbo because the results do not necessarily mean the patient won't develop cancer; rather, the results are not very informative.”

Part of Walker's work involves collecting these unresolved cases from around New Zealand and working with international colleagues to understand their significance.

“Ernest Rutherford said, 'We've got no money, so we've got to think.' I think we have to go further than that. We've got no money so we have to collaborate,” Walker says.

One of his collaborations is as the only New Zealand member of the ENIGMA consortium, an international network of researchers working together on large-scale analyses of neuroimaging and genetic data. To become part of the exclusive group, researchers have to be accepted on the merits of their work.

“I can contribute data from New Zealand to these large studies but I can bring much more back. I inherit the tens of millions of dollars invested in these genome studies.”

The group is named ENIGMA because DNA is a big code, and members such as Walker aim to decode it.

“We are pulling cases out of the 'too-hard baskets' and collating these from all around the world. We are trying to define these and are successful in a lot of cases.”

The ultimate goal is to be able to identify the people most likely to develop cancer.

“If you think of cancer patients who are being treated as being at the bottom of the cliff. There are certain people who are more likely to fall over the edge. We want to catch them before that happens, and if possible, get them the most appropriate treatment to stop or delay that fall.”

Funding

- Rutherford Discovery Fellowship (Royal Society of New Zealand)

- Mackenzie Charitable Foundation

- Health Research Council

- New Zealand Breast Cancer Foundation

- Breast Cancer Cure

- Canterbury Medical Research Foundation

- Cancer Society (Canterbury/West Coast)