Thursday 25 July 2019 5:46pm

As a series of forums begins nationally this month to hear from New Zealanders harmed by medical procedures using surgical mesh Jacqueline Brown, whose recent Master of Chaplaincy thesis discussed the topic, says there is a “clear gap” in the literature around this significant issue.

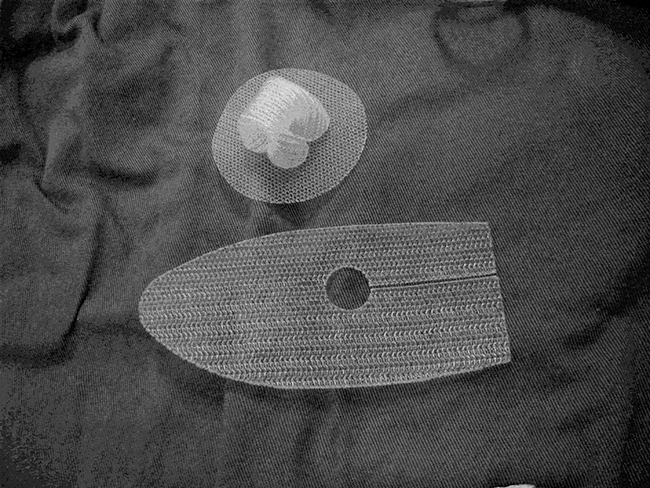

Surgical mesh is used in hernia repair, pelvic organ prolapse, and stress urinary incontinence. Since 2005, ACC has paid out more than $23 million in compensation for mesh-related claims.

As the first restorative justice “listening circle” in Wellington started on 24 July, Stuff reported the 340 people had registered to attend forums – whereas the Ministry of Health had estimated only about 180 would attend.

Jacqueline Brown

Brown says her thesis, entitled A Thorn in the Flesh: The Experience of Women Living with Pelvic Surgical Mesh Complications and research points to a clear need for more qualitative research around surgical mesh complications.

The 'listening circles' remind Brown of the principles of the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission process which she studied as part of her master's; but she says while listening is important "action is more important."

"After the Ministry of Health has listened they need to act, not just to prevent future harm but to provide practical and ongoing support to those whose lives have been affected my mesh complications up to this point.”

What prompted your interest in this topic?

My own experience of pelvic surgical mesh injury.

How did the Master of Chaplaincy allow exploration of this issue?

I didn't choose the MChap as a way of exploring the issue, I was doing the MChap with the intention of working in chaplaincy. The research paper MINS590 was part of the course and I wanted to research a topic that would keep me engaged for a year, and that would contribute to knowledge and understanding of an area about which little was known. In essence it was important that whatever research I did made a difference.

In your abstract you refer to a gap which exists in the literature concerning women’s lived experiences of these complications – what needs to be done to further discussion of this important issue?

I don't just think a gap exists, there is a very clear gap in the literature. The existing literature is predominantly clinical and quantitative in nature, often using anatomical outcome measures as a measure of success. The voice of the women who experience complications is not sought or heard in this type of research. Qualitative research makes this possible.

What were some of the complications the women reported, and how did this impact on their lives?

The women in my research had experienced the same complications outlined by the FDA in 2008 - mesh erosion through the vagina, pain, infection, bleeding, and pain during sexual intercourse, organ perforation, urinary problems, neuromuscular problems and vaginal scarring/shrinkage. The impact of these complications on the women's lives was far reaching. They found that they could no longer rely on their bodies, and that they must make significant changes to their day-to-day lives to continue to function. Family systems are affected as they are unable to perform their former roles, be an equal relationship partner, and economic impacts from loss of employment causes a drop in their standard of living. They experience cumulative losses and associated grief. They find themselves stuck in the 'now', unable to return to their pre-mesh selves, or to participate in the taken-for-granted futures that they formerly perceived for themselves.

What did integrating spirituality into their coping mechanisms offer in terms of support?

Some women found comfort in God and this helped them find meaning and hope in their suffering. For others their families were a source of strength and what kept them going when their suffering seemed unbearable. Three of the seven women had considered taking their own lives, and two had diagnosed PTSD, so having hope and something to live for was important.

Were there any surprise or unexpected findings?

The degree of loss across so many areas of the women's lives, and the detrimental impact on a person's hope when they perceive that medical practitioners and government agencies do not care about their suffering.

Did women report faith-based interactions as important in the post-surgery period/ were the mechanisms for them voicing their issues adequate?

I didn't specifically look at faith-based interactions post-op. Many of the women were told that it was "all in their head" and had poor responses from their medical practitioners when they raised concerns about their symptoms. This was also supported by the Australian Senate Inquiry. The assumption is often made by medical practitioners, and sometimes the women, that if the problem cannot be found in the body it must be in the mind. Only one of the women in my study had a positive experience with ACC, three of the other women underwent multiple reviews to get their treatment injury claims accepted. Two of the women have diagnosed Post Traumatic Stress Disorder related to trauma experienced in relation to their medical treatment and subsequent complications.

What would you like to come from this research re social engagement, or wider debate/ understandings of the issue/ pastoral care?

I think that we need more qualitative research in all areas of health to better reflect the impact of treatment as experienced by the persons receiving treatment. We need to comprehend that what we do to the body we do to the person.

Understanding the meaning that people attach to their experience and the disruption to their lifeworld is crucial to any healing process.

We should encourage, lament, listen and learn from it. Sharing these insights with the healthcare team, and those who regulate and have oversight of the healthcare system can help inform policy and practice that enables embodied-person-centred care. At the heart of pastoral theology in healthcare is the knowledge that while cure may not be possible, or healing certain, care is always possible.