Tuesday 21 July 2020 11:28am

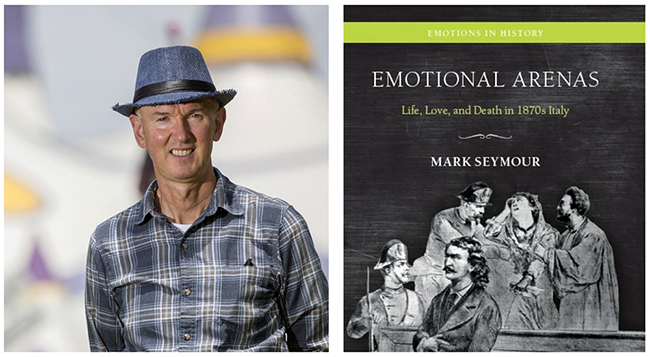

History programme Associate Professor Mark Seymour says stumbling across 1870s love letters received by an Italian circus acrobat from various women who fell madly in love with him sparked research leading to his new book Emotional Arenas.

The book, released by Oxford University Press last month, explores whether emotions and their expression change over time and, if so, how historians discover and discuss these changes.

Seymour, who studied European history and Italian language as an undergraduate student, says his research on marriage, extramarital affairs and divorce got him thinking about what he dubs “emotional arenas” – and suggested the book's title.

“My basic idea is that emotions are often prompted, or curtailed, by particular social spaces. Spaces of all types tend to make people feel in certain ways: we pick up cues and behave in particular ways. If people are at a stadium when the All Blacks win, they can emote in a way that they would never do in, say, a lecture theatre, because the space gives them cues about what they can do in terms of expressing their emotions."

Why did you undertake research in this area, and the publication project?

I’m a historian of nineteenth-century Italy and this book is based on a chance ‘find’ in the archives – a bit like an archaeologist chancing across an epoch-defining skull. What I found were the investigation records of a murder that took place in Rome in 1878. Initially I wrote two articles on the trial, but felt the material could be the basis of a good book: it allowed me to tell a story that transcended the national confines of Italy and moved into a more universal realm.

What is it about?

On page one of the book, a murder takes place just near Rome’s Colosseum. I then take the story both backwards in time, to find out about the lives of the victim and the people around him – he was a decorated soldier of Italy’s 1860 unification. And I also take the story forward, to the murder trial, which transfixed Italy and many other places too – even New Zealand newspapers reported on the trial. The reason for this fixation was the story revealed by the murder: the soldier’s wife had fallen in love with a circus acrobat, and together the illicit couple conspired to get rid of the soldier so they could marry.

What was it about the famous 'love-triangle' that scandalised Italy at the time? Was it a distraction from, or somehow amplified by unification?

Well I suppose that even today if a woman commissioned her lover to murder her husband there’d be a bit of a scandal, though it’s not unthinkable. Back then, it was unthinkable. And it was very rare for a given couple’s sex lives to be turned inside out for inspection by the nation, so there was a very eager audience. Moreover, an almost unspeakable conundrum lay at the heart of the matter: it turns out that the soldier had been made impotent by a battle wound acquired in the name of unifying the Italian nation. He was unable to procreate, and that made the marriage very problematic in a Catholic culture – but he had sacrificed his ability to procreate for the sake of the Italian nation. This made the story into a huge moral dilemma, and in this sense, it was very much amplified by the question of Italian unification – marriage and the nation were intimately and awkwardly entangled in the story.

What made you think of developing the “emotional arena” as a paradigm for analysing private and public emotions in relation to types of social space?

The police, when they were investigating the murder, found a cache of highly emotional love letters from female admirers, collected over the years and safely hidden in the circus acrobat’s travelling trunk. I read these and was really struck by their intense emotionalism – especially since the standard historical image of nineteenth-century Italian women is modelled on the Virgin Mary. Normally such sentiments, especially those experienced by ordinary and anonymous women, are almost impossible for historians to trace. Reading those letters made me wonder about the way cultures of emotion change over time – they made me wonder whether emotions themselves have a history. I began asking myself these questions in around 2008, just as the history of emotions was developing as a subfield, and I wanted to contribute to the debates. Quite early on I came up with the paradigm of the emotional arena as a framework for investigating the historic role of distinctive social spaces – such as opera theatres, churches, confessionals, the town square, the bedroom, the courtroom – in the generation and ‘staging’ of emotions. It is difficult for historians to trace emotions in the past, but looking at the relationship between emotions and public spaces gives us a more concrete way of visualising historical change in this area of human experience.

I hope reading this book makes people think about . . .

The powerful role of emotions in life, in the law, in nations, and other genres of human community.

You should read this book if . . .

. . . any of the above tickles your fancy!