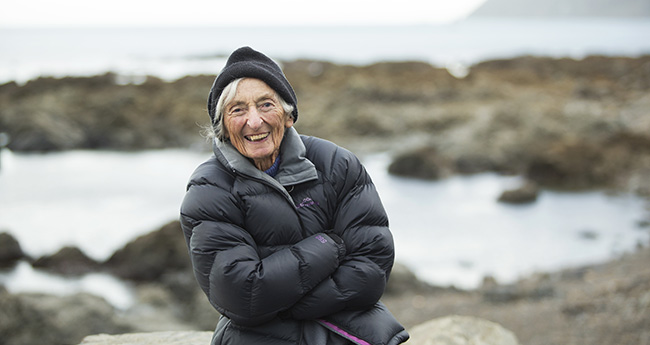

Force of nature

A life-long interest in both words and the great outdoors has shaped the life and career of Otago alumna Sheila Natusch.

The beaches that stretch westwards from Wellington airport, bravely countenancing the whitecaps of the Cook Strait, resemble more the rugged coastline of the island they face than the one they cling to. It is an appropriate place for Sheila Natusch, the intrepid, Invercargill-born writer and illustrator, to call home – one foot washed by the waves and the other wandering the untamed hills.

Wild, remote places run in Natusch's blood: her paternal grandfather came to New Zealand from Orkney and, after his World War II service, her father became a ranger on Stewart Island. It was there she grew up, in and amongst a nature unpackaged and unframed.

Natusch's maternal grandmother and her mother were both painters of landscape, flora and fauna. From these women she learned to capture the moments of nature in a few deft gestures – the slate-grey back of a fish hanging just under the sea surface, the hurried footsteps of a dotterel on a beach. But she also developed a love of language and a desire to record places and people, not just in pictures, but also words.

Natusch's career, recognised in 2007 with a New Zealand Order of Merit, spans more than 60 years. Her many books include Animals of New Zealand and The Cruise of the Acheron – the first published account of the voyage of the ship that surveyed the coastline of New Zealand from 1848 to 1852 – but she has written and/or illustrated more than 30 titles in total. These include a biography of her great grandfather – a German missionary who lived on Ruapuke Island – as well as a history of early Southland women and many accounts of her adventures in nature.

Natusch still writes, paints, draws and corresponds from the same home on the hill overlooking the sea that she shared with her hydro-engineer husband, Gilbert, for 55 years. She only recently relinquished daily outings around the bay in her small inflatable yacht and still mourns the paua breakfast she used to enjoy before the Taputeranga Marine Reserve was established. At 89, she is still a woman to be reckoned with.

The singular force of nature that was born Sheila Traill was shaped by a childhood spent either accompanying her father on his forays around Stewart Island or “coasting round and noticing plants”.

“I suppose as I got taller,” says Natusch, who stands at little more than 152 centimetres tall, “I took more of an interest in trees and shrubs.”

“'Natural history',” she writes in 'An Island Called Home', “was an expression I heard used from early childhood: it ran in the family. But I do remember wondering what history had to do with it. History was kings and canoes and ships that went exploring and it belonged to school; natural history was lampshells and seahorses and ferns and vegetable sheep and belonged not to school, but to the outside world of holidays and spare time.”

Natusch's abiding interest in both words and the great outdoors led her to the University of Otago where she studied natural sciences, languages and literature from 1943 to 1946. She graduated with an MA (Hons) in 1947, having also trained at Dunedin Teacher Training College.

While in Dunedin she worked part-time at the Botanic Garden, tramped in the hills to collect rocks and plants, and became friends with fellow observer Janet Frame, with whom she shared the great love for words that is evident in her own characterful writing.

“I like poetry,” she says. “Shakespeare. Milton. Chaucer. But Wordsworth I can take or leave. Professor Ramsay [Herbert Ramsay, longstanding Chair of English at Otago] said Wordsworth always stands in front of his landscapes.”

Sheila Natusch: “It was daunting at first, to find myself among august characters known to me only as names on textbooks and in learned journals."

Not one to stand in front of anybody or anything, Natusch found she was not suited to the classroom, so opted to teach in the Correspondence School – perhaps also because she felt an affinity with those who live in outposts. She had also worked as an assistant at the National Library, where she recalls being reprimanded by librarian A. G. Bagnall for doodling on the back of index cards.

The progression from teaching and bibliographic work to published writer and illustrator seems a logical one that met Natusch's clear impulse to explore, describe and depict the world around her and what happened in it. She writes and draws not as a Wordsworth, standing out in front of her subject, but as an eager participant, immersed in it.

To point out the difference between the work of a nature illustrator compared with that of a nature photographer, Natusch recalls a conversation with New Zealand's iconic literary agent Ray Richards.

“When I was working on Animals in New Zealand I did a picture of dotterels scurrying along the beach so fast their legs were a blur. Ray said 'is this bird with us or not?' I think he wanted to see every scale and every toenail, but I just drew what I saw.”

Natusch is a longstanding member of the Royal Society of New Zealand and for a long time represented Southland on the society's standing committee. She recalls setting off on stormy nights for Wellington meetings “in gumboots, fighting my way through bushes and boulders and great hunks of earth, then catching a tram to get to wherever they had the meetings. The men would be wearing their suits and there was I, all washed up.

“It was daunting at first, to find myself among august characters known to me only as names on textbooks and in learned journals. I did have trouble being the only woman, a small person with a small voice soon drowned out by stronger masculine utterances. When I wanted to say something I had to build myself up to coming out with it, only to subside unnoticed. So I took to writing memos to the new young president, putting the case for small groups eager to learn about science, though they could not be considered scientists.”

Asked if she is a feminist, Natusch is characteristically down-to-earth: “No, I'm just a person.” But whether she is a feminist or not, strong women undoubtedly have had a strong influence on her. She was educated at Southland Girls' High School (and believes she currently holds the status of their oldest living “old girl”) during which time she lived term-time with her father's older sister in Invercargill.

“She was a great observer, but strict, and she tried to civilise me. Saturday mornings were for dusting and she would always find places I had missed.”

Natusch's own house, she says, is “chocka with books and papers” and she has neither time nor space for a television. She rues the substitution of upbringings like hers – in the great outdoors – with the indoor variety.

“I used to like seeing kids on rocks fishing. They would hardly ever catch anything, but the fact they were just sitting there was nice.”

Such sentiment is evident in Pop Kelp and Poha Bags, a small activity-style volume aimed at enticing children to explore the small wonders found on our beaches. Although aimed at children, it demonstrates the wonder and curiosity that lies at the heart of all her work for the spaces that can be found outside our doors and the things that inhabit them.

“Rock pools are good because you see the creatures darting about and you can put your fingers in. Now kids get all their wildlife on TV and it's not local either. There are all these nature programmes, but there's plenty of nature just outside the door.”

A life spent exploring places is a life well lived – and is certainly “so far, so good” as Natusch titled her “autobibliography”.

“Whether those 'places' are a tiny hut, a village, an island or larger landmass, a hemisphere, or 'the great globe itself', seeing it in proportion and in perspective helps us to keep balance in other ways. And to do that, you have to get your own feet wet.”

Sheila Natusch talks about her life and work. (Thanks to Radio New Zealand National)

Story: Rebecca Tansley | Photo: David Hamilton