Pioneering

nutritionist

on a mission

While she's not exactly a household name, the influence of Dr Muriel Bell on New Zealand's public health policies is far reaching. Now, the collection of her papers housed at the Hocken Library have been inscribed in the prestigious UNESCO Memory of the World New Zealand Register.

“The way to pioneer a new subject is to have a pioneer lineage, on both sides of the family!” So said Kiwi medical researcher and nutritionist Dr Muriel Bell – New Zealand's first state nutritionist whose pioneering work radically improved the standard of nutrition in New Zealand and was responsible for ground- breaking public health schemes such as milk in schools, the iodisation of table salt to prevent thyroid disease and public water fluoridation to combat tooth decay.

Distinguished by her biographer Diana Brown for her “unconventional career”, Bell was one of the first New Zealand women to obtain the research degree of Medical Doctor. She studied physiology and biochemistry at the University of Otago, with a focus on the newly established connections between disease and nutritional deficiencies, leading research on vitamins and minerals to prevent deficiency diseases and, later, optimise health. Her early research into fats and cholesterol tackled the complexity of nutrition-related aspects of coronary heart disease.

Driven by a deep social concern, especially for the health of women and children, Bell's nutritional advice – shared through radio talks, nutrition handbooks and her regular column with the New Zealand Listener – may be commonplace today, but was revolutionary at the time, such as: eat more fruit, vegetables and milk products, and cut down on sugar, fat and meat. During her 24-year tenure as state nutritionist (1940–1964), she increased scientific knowledge of nutrition and helped establish nutrition and dietetics as professional fields in New Zealand.

Muriel Bell was born in Murchison on the West Coast in 1898. Her parents (Thomas and Eliza) farmed and operated a sawmill. They also gave advice and medical help to the growing community – her father stitched wounds and set broken bones.

Says Bell: “The honour goes to my mother who gave me a strong body and to my father who acquired a great deal of medical knowledge from reading medical books – there was no doctor within 70 miles and he used to be a sort of doctor for the district we lived in, so I had the benefit of cod liver oil and such like in my childhood.”

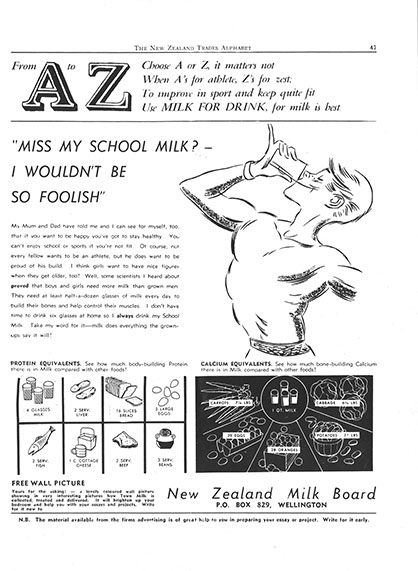

Dr Muriel Bell's conviction that milk was a vital food source led to a nationwide programme of free milk to school students. Milk in Schools, MS-1078/001, Muriel Bell papers, Hocken Collections Uare Taoka o Hākena.

In 1907, when Bell was nine, her mother was killed in a tramcar accident in Wellington. The family moved to Richmond and Bell eventually attended Nelson College for Girls, before winning a university scholarship and moving to Dunedin to study medicine, originally planning to become a medical missionary.

With women medical students still unusual in the early 20th century, she was one of a “close and friendly group of seven or eight women among only 30 students in all” who began their medical training in 1917 – receiving a mixed reception from the establishment.

She later reflected: “Women were not altogether welcomed at the time, as medical students. Engraved on the desk that I sat in was the slogan 'Women's place is in the home'.”

In 1922, Bell graduated from medical school, but decided to stay on and do research on human metabolism. Particularly concerned with the thyroid gland in people suffering from goitre, her research contributed to the introduction of iodised salt – showing that increasing the level of iodine in the diet was an effective protection against the illness. In 1926 she became New Zealand's second woman to be awarded the research degree of Doctor of Medicine (MD) – the first was Dr Margaret Cruikshank who obtained an MD at Otago in 1903.

Over the next decade, Bell's award-winning work saw her hold a range of positions including lecturing at the Otago Medical School and conducting nutritional research into, for example, the role of vitamins (while based at University College London) and soil deficiencies. On returning to Dunedin in 1935 to lecture in physiology and experimental pharmacology, she later became a founding member of the Medical Research Council, serving on its nutrition committee alongside her role on the Board of Health as its only female board member at the time.

In 1940, she took up the position of New Zealand's first Nutrition Officer in the Department of Health alongside Director of Nutrition Research at Otago Medical School. Over the war years, the government frequently consulted with Bell about food rationing and, when shipping losses cut down New Zealand's supplies of cod liver oil (at the time given to children because it contained vitamin D), she found an alternative source of vitamin D in New Zealand fish oils. She developed a recipe for making rosehip syrup so that children could get vitamin C when the supply of oranges ran out.

Later, when she became concerned that vitamin C and riboflavin in milk are destroyed by exposure to sunlight, it became a requirement that milk delivery vehicles were covered. She also worked to have milk pasteurised and have unhealthy cows destroyed. Her conviction that milk was a vital food source and should be part of New Zealanders' daily diet led to a nationwide programme of free milk to school students.

Another ground-breaking initiative was in showing a link between fluorine and good teeth, campaigning long and hard as “Battleaxe Bell” for the introduction of fluoride into town water supplies. This led to massive reductions in tooth decay across generations of New Zealanders.

As Bell eloquently describes in her essay titled “The Work of the Nutrition Research Department”: “The sun of hope for better teeth has already risen over the New Zealand horizon… For the first of these two decades it was a voice crying in the New Zealand wilderness, but today sees the expansion of the idea of mineral deficiencies affecting the resistance of teeth to decay.”

Muriel Bell's desire to build sound nutritional knowledge across the population meant she committed much of her time to sharing advice and research in various articles, interviews and guidelines. As her biographer puts it, “Muriel understood, nutrition is a cornerstone of individual and public health. Nutrition researchers, nutritionists and dieticians have a vital role in shaping the health of New Zealand.”

“The sun of hope for better teeth has already risen over the New Zealand horizon… today sees the expansion of the idea of mineral deficiencies affecting the resistance of teeth to decay.” – Dr Muriel Bell

Early on she helped create the handbook Good Nutrition: Principles and Menus (1939), followed by Normal Nutrition – Notes for Nurses to help nurses care for patients better. Her contributions to The Listener explained in everyday language the latest research in nutrition – everything from “The Nutritive Value of Potatoes” to “A Talk on Liver” or advice for parents about how to feed their babies cod liver oil or arguments for milk as “our best single food”.

As Bell put it in an essay titled “Nutrition Research”: “A great many people have enquiring minds that make them want to know whether they are doing the right thing by themselves or their families and though it isn't always a good thing to be fussing about either health or foods, it's good to see whether there is from time to time any 'news from the stomach front' and then put its items into practical effect in one's daily habits, but keep them somewhere in the back of one's consciousness.”

According to her biographer, many of the current topics in nutrition research bear a “striking resemblance” to the range of projects that occupied Muriel Bell throughout her career, “reminding us malnutrition and nutritional deficiencies are still a major concern”.

Muriel Bell died in 1974. In 2020 the Muriel Bell papers, held by the Hocken Collections, were accepted to the UNESCO Memory of the World Register. The register lists inscriptions of significant documentary heritage that contribute to New Zealand's history and heritage, and are significant to the identity of New Zealanders today – a feat no one would argue Muriel Bell achieved over her career.

Yet despite the volume of papers and materials that share the life of Muriel Bell, she remains a somewhat enigmatic figure. Little is known of her personally, says Diana Brown.

“We can discover little for example about how the early deaths of two siblings and her mother might have affected her. She married twice, both times to men many years older than she was; beyond the knowledge that they, most unusually for the time, took on the primary housekeeping duties.”

What we do know of this remarkable pioneer is that Muriel – who was awarded both a Fellow of the Royal Society of New Zealand and Commander of the British Empire – became a missionary in her own country. As her friend Marion Robinson described: “Dr Bell did become a medical missionary, but in a somewhat unusual way – as a home missionary bringing good nutrition to everyone through New Zealand.”

AMIE RICHARDSON

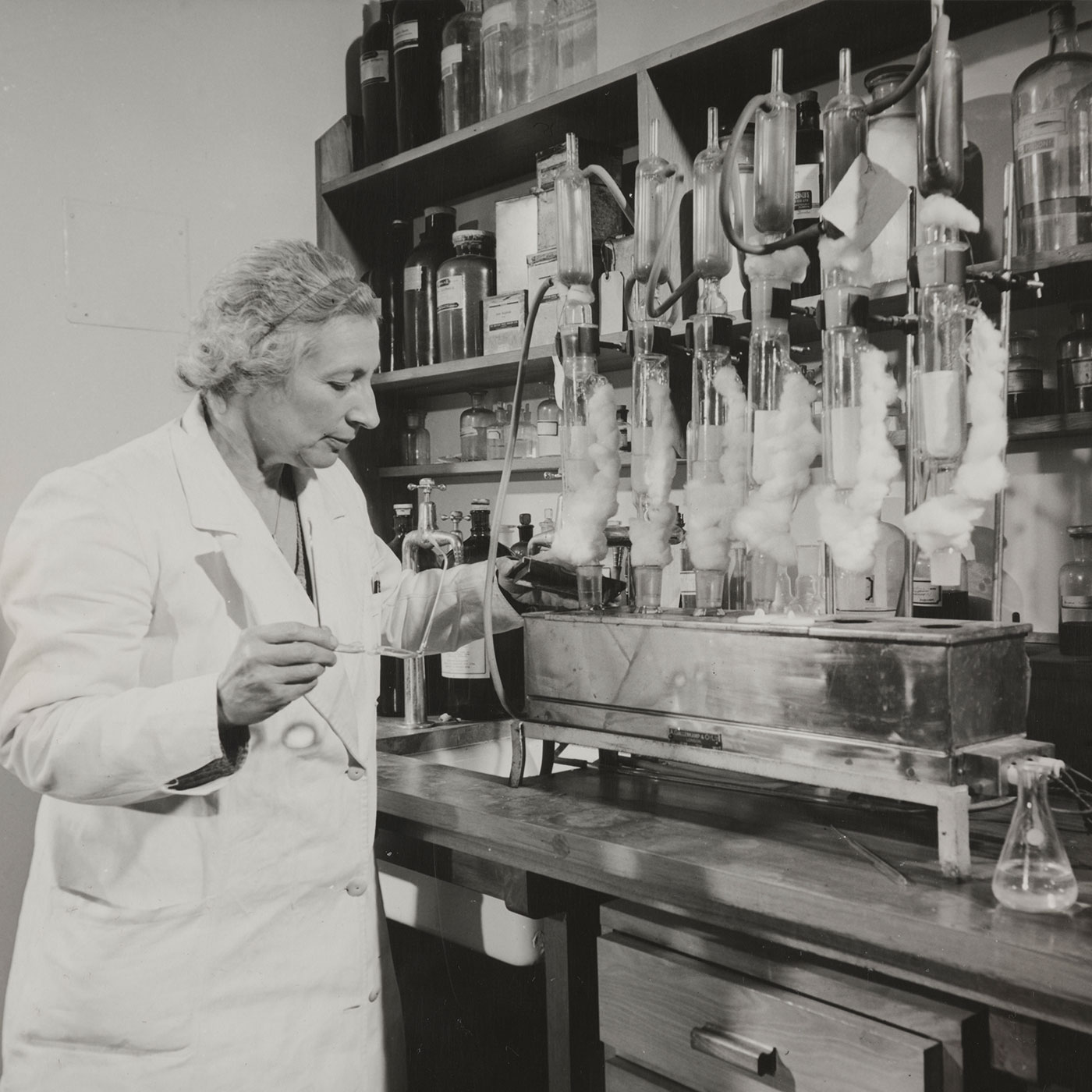

Dr Muriel Bell was only the second New Zealand woman to obtain the research degree of MD. Prime Minister's Department photograph, Box-184-127, Hocken Collections Uare Taoka o Hākena.