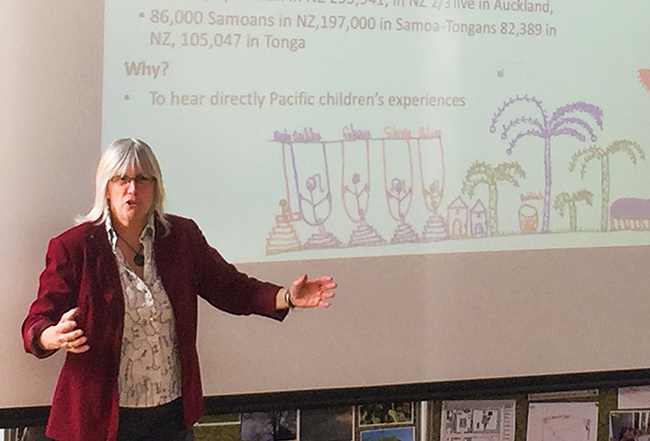

Professor Claire Freeman thanks "Tamaiti ma suiga i le Pasefika: Childhood in a changing Pacific" research participants at the Dunedin campus in early November.

Three Division of Humanities staff have secured Marsden funding for research projects.

University-wide, researchers secured $17.5 million for 30 world-class research projects with fourteen projects from each Division receiving grants ranging from $729,000 to $960,000. A further 16 researchers received $300,000 fast start grants.

Division of Humanities Pro-Vice-Chancellor Professor Tony Ballantyne congratulated recipients Professor Claire Freeman (Geography), Dr Erica Newman (Te Tumu: School of Māori, Pacific and Indigenous Studies) and Dr Karen Greig (Archaeology).

Professor Tony Ballantyne

“I am delighted with the outcome of this year's Marsden applications, for the individual researchers who have been successful, for their academic programmes, and for our Division as a whole. Getting through to the full Marsden round and then winning a grant is an extremely significant achievement: it is a great endorsement of the researcher's ability to frame a compelling research question and the funding enables them to pursue important new lines of investigation for a sustained period.

“This year's successful projects underscore the Division's very real strengths in New Zealand and Pacific research and these projects are grappling with compelling questions. I know that all of us in Humanities at Otago will be delighted for Karen, Claire, and Erica.”

Professor Claire Freeman, Geography, Negotiating Childhood around the Pacific-Rim: A multi-generational analysis - $729,000

Professor Freeman, with Professor Sarah Turner from McGill University (Canada) and Dr Helen Woolley from the University of Sheffield, will ask “is the 21st century a good time to be a child?” and “what action should governments and planners take to shape the places where children live?”

The researchers will adopt a newly developed 'child-centred multi-generational family approach' to examine how childhood has changed in the last three generations for many children in the Pacific-Rim due to increasing urbanisation, rural to urban migration, changing mobilities and technologies.

Through a novel combination of interviews, focus groups, Geographic Information Systems and childhood narrative maps they will identify how societal and built environments have changed over three generations, specifically examining childhood impacts and the factors supporting or inhibiting wellbeing. The research will focus on children, parents and grandparents living in three-generation families in five Pacific Rim countries: New Zealand, Samoa, Vietnam, China, and Japan.

They will identify the 'immutables' – core childhood factors that create and support wellbeing irrespective of time and space – and those that are locationally and culturally distinct. Through collective data gathering and story sharing, they aim to empower families and support professionals to identify ways that children's lives have changed at family and neighbourhood levels.

“Very little comprehensive research has been undertaken to understand what urban environmental change means not only for children but also for families and wider society. What type of environments do we need that enable children and their families to thrive? In addition, are there ways that different cities' responses to their own imperatives can be shared to better inform children's urban developmental futures elsewhere around the Pacific Rim? This research will inform and encourage urban planning and development that supports positive child-friendly futures,” Professor Freeman says.

Dr Erica Newman, Te Tumu: School of Māori, Pacific and Indigenous Studies, Journey Home: Descendants of Māori adoptees search for their tūrangawaewae Fast Start Funding – $300,000

Dr Newman's project will explore what it means for descendants of Māori adoptees who have no knowledge of their Māori heritage, and the effect the absence of tūrangawaewae has on their identity, their health and their wellbeing.

Dr Newman

“Finding whakapapa connections can benefit and strengthen their Māori identity by knowing who they are and where they come from. Focusing on these descendants and following them on their journey home, this project will explore; how they identify with their taha Māori, avenues undertaken to connect to their tūrangawaewae, and how they are accepted by their whānau and hapū.”

Oral narratives will be the primary base for this project, while a private Facebook page specifically for descendants will provide ongoing support as they begin, or continue, their journey searching for their taha Māori. As the first project to focus on the descendants of transracially adopted Māori adoptees, this research will advance a new direction within the field of transracial adoption globally through an international symposium and a monograph.

Dr Newman says between 1955 and 1961 (the last year the New Zealand Official Year Books specified adoptions between Māori and non-Māori), 13,605 legal adoptions took place. Of these, 1,880 were Māori; it is unknown how many of this number were transracially adopted.

“While we do not know the number impacted, we do know that transracial adoption has created 'ghosts', known and unknown, both within the whakapapa and for the adoptee and their descendants. Not being able to say your pēpeha, or your entire whakapapa, identify your marae, and your tūrangawaewae is the very real outcome of the 1955 Adoption Act for a Māori child raised in a non-Māori household, and for their descendants, when they have not been able to establish a connection to their taha Māori.”

“This research is socially significant as it will bring to light the consequences of transracial adoption on identity and well-being for adoptees and their descendants in Aotearoa New Zealand as they journey home.”

Dr Karen Greig, Archaeology, Pigs, dogs and chickens and the quest for status and prestige in the Pacific past. Fast Start Funding – $300,000

Dr Greig's research will examine how domesticated animals, especially pigs, have been important items of exchange between networks of communities across the Western Pacific.

“Their use as a food item is often secondary to their role in social interactions, where status and wealth could be obtained and manipulated through the exchange of valuables. But our understanding of the role of animals in the development of these networks has been extremely limited.”

Recognising the importance of exchange in Western Pacific social systems, archaeologists have long been interested in understating their development and change over time. The immediate origins of some of the well-known nineteenth century Western Pacific networks has received archaeological attention, including the hiri, kula, Siassi, and Madang networks. The mass production of pottery and the rise of specialised 'middlemen' in these maritime trade monopolies, in operation at the time of European contact, have been linked to increases in population density, environmental decline, and variable access to resources. Looking back further, archaeological research has focussed on reconstructing exchange networks by tracing the sources and distribution of inanimate objects, such as stone tools, pottery, and shell valuables.

“What is missing in archaeological studies of exchange, despite the ethnographically documented importance of animals, is a consideration of the role of pigs, dogs and chickens in these networks. This is critical – without it, we lack a complete picture of how the networks functioned and changed,” Dr Greig says.

This dearth of attention is not due to a lack of interest, but rather to the challenging nature of studying animal bones from tropical Pacific archaeological sites. Material culture objects (stone tools and ceramics) are durable and amenable to geochemical analyses to pinpoint their place of origin.

Archaeologists have used stone and pottery artefacts to study exchange networks as they survive well in tropical Pacific sites and can be traced from where they were made to their final resting places. By comparison, studying animal bones is challenging. They are fragile and even if present, they are often highly fragmented and difficult to identify, let alone determine where they may have come from.

“We will use exciting new biomolecular techniques to identify pigs, dogs and chickens in the archaeological record, examine human-animal interactions and animal husbandry practices, and detect change through time. This research will contribute to understanding the cultures and history of Western Pacific, and to the wider story of human-animal relationships and their place in human societies, from the past to the present day.”

(Below: Dr Karen Greig)