Thursday 29 September 2022 2:27pm

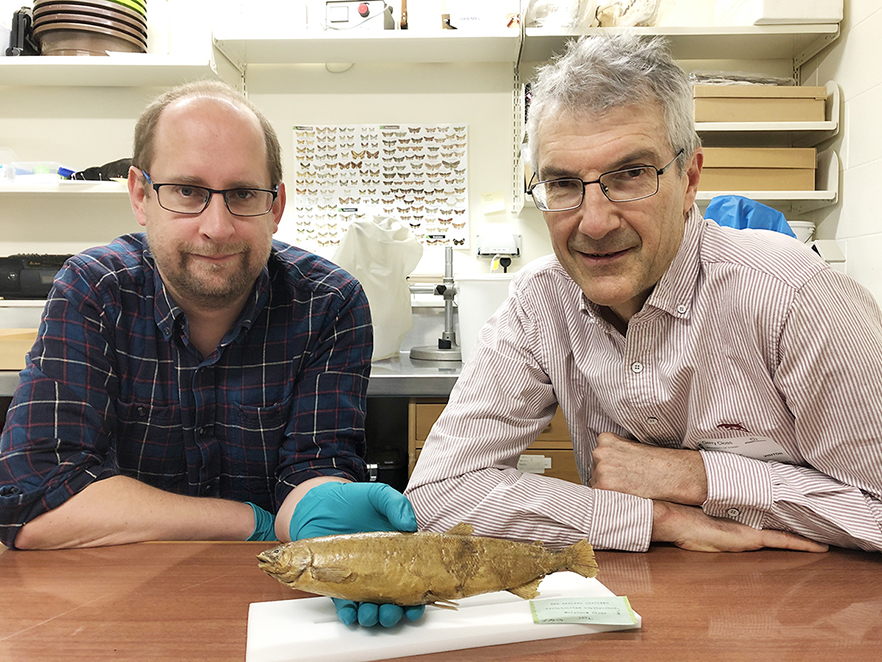

Dr Nic Rawlence and Professor Gerard Closs with an upokororo/New Zealand grayling specimen at Otago Museum. Image Credit: University of Otago

Nearly 100 years after its last confirmed sighting, University of Otago researchers have revealed the genealogical story of the upokororo or New Zealand grayling.

Study co-author Dr Nic Rawlence, of the Otago Palaeogenetics Laboratory, says very little is known about the extinct fish, with only 23 specimens known in museum collections.

Its claim to fame is being the only known fish to have gone extinct in Aotearoa after the arrival of humans.

“It is one of New Zealand’s most enigmatic extinctions – from hyperabundant in the 1800s where ‘cartloads’ containing thousands of fish were caught and traded, it was rare as hens’ teeth by the early 19th Century with the last confirmed sighting in 1923.

“It died out due to overfishing, habitat destruction, disease, and predation. In true Monty Python-style it was protected only after it was no doubt extinct,” he says.

To better understand the poorly fated species, study lead author Lachie Scarsbrook, a PhD candidate at the University of Oxford who completed a Master’s of Science at Otago, sequenced mitochondrial genomes from rare specimens of upokororo and reconstructed their evolutionary history.

The study, published in Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, outlines how the Australian grayling is the closest living relative of the fish, but a distant cousin at best – they diverged over 15 million years ago, with their ancestors likely arriving in Aotearoa between 15 and 23 million years ago.

“This suggests that the tupuna ancestors of upokororo arrived in Aotearoa via long distance dispersal following the birth of the Alpine Fault, which caused uplift of land, and development of rivers, after most of New Zealand sunk beneath the waves during the Oligocene ‘drowning’,” he says.

Some scientists have previously put forward the idea that the Australian grayling could be introduced to Aotearoa to fill the ecological gap left by the extinction of the upokororo.

However, Mr Scarsbrook says this is not a good idea as the millions of years of independent evolution mean the roles they fill in the ecosystem are likely very different.

“In evolutionary time, it’s equivalent to replacing you with an orangutan. You can only imagine the issues your workplace would run in to,” he says.

With global fish populations in sharp decline, the researchers hope lessons learned from past extinctions can help us preserve fish species for future generations.

Study co-author Dr Kieren Mitchell, of the Otago Palaeogenetics Laboratory, says new advances in ancient DNA techniques are now unlocking the genetic secrets of more museum specimens than ever before.

“Genetic research on old ‘wet-preserved’ specimens treated with chemicals like formaldehyde has previously been very challenging.

“Continuing this research in the future by sequencing the nuclear genome of the upokororo – its complete genetic blueprint – could potentially reveal more about how its ancestors changed and adapted after arriving in Aotearoa and provide more clues about the exact cause of its extinction.”

Publication details

Ancient DNA from the extinct New Zealand grayling (Prototroctes oxyrhynchus) reveals evidence for Miocene marine dispersal

Lachie Scarsbrook, Kieren J. Mitchell, Matthew D. McGee, Gerard P. Closs, and Nicolas J. Rawlence

Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society

For more information, please contact:

Dr Nic Rawlence,

Director, Otago Palaeogenetics Laboratory

Department of Zoology

University of Otago

Email nic.rawlence@otago.ac.nz

Lachie Scarsbrook

Palaeogenomics and Bio-Archaeology Research Network

School of Archaeology

University of Oxford

Email lachiescarsbrook@gmail.com

Ellie Rowley

Communications Adviser

University of Otago

Mob +64 21 278 8200

Email ellie.rowley@otago.ac.nz