Retired GP Ben Gray has from sandal-wearing to teaching medical students how to dress.

It was a while before young GP Ben Gray gave in and started wearing socks to work.

The GP turned academic, sees some irony in the fact he's now teaching dress code to the next generation of doctors.

“I wouldn't have met any of the dress code that I'm recommending [to medical students],” says Dr Gray.

"I won't miss the ever-increasing accretion of bureaucracy, regulations, rules and ways of claiming funding"

“I wore sandals, had long hair and a beard and generally, in retrospect, I can see that I was a bit uncomfortable being moulded by the medical world into someone I wasn't sure I wanted to be.

“So I was yelling 'I'm not one of you'.”

Thirty-five years later, he is retiring proudly as “one of them”. A card-carrying, passionate and individual GP who served first in the Taranaki town of Waitara and, for the past 27 years, at Newtown Union Health Service in Wellington.

Although no longer a practising GP, he continues as an associate professor in the primary health care and general practice department at the University of Otago, Wellington.

In the early 1980s, sandal-wearing Dr Gray trod a path different to most doctors of the day.

As a house surgeon in Taranaki, he was the doctor for the 1981 centennial commemorations of the invasion of Parihaka. “I stole a lot of stuff from ED and fitted out a caravan, and was on site as the doctor,” he says.

Then he volunteered to be the typist for Taranaki iwi Te Āti Awa's ground-breaking Waitangi Tribunal claim and campaign to stop the Motunui synthetic fuel plant discharging waste into local fishing grounds.

Looking back, he sees his interest in environmentalism and things Māori was seeded by inspirational teachers at the then newbie Wellington School of Medicine.

A key role model was physician and researcher Ian Prior, one of the drivers of the Save (Lake) Manapouri campaign, who did pioneering epidemiological research with the Tūhoe communities in the Urewera.

Other influences included Jules Older, a US-born University of Otago behavioural science lecturer, who spoke up in the late 1970s for more Māori in the health professions. Dr Older got flak for it.

Activism, then, rather than medicine, dominated the early 1980s for young Dr Gray.

A couple of years at Taranaki Base Hospital showed him hospital medicine was not for him, and he decided on general practice.

After his GP registrar training year, he asked to join the group practice in Waitara – the north Taranaki town where he already had links through his involvement in the Motunui case. Tribunal work was part of developing his role as a doctor.

His Māori patients couldn't gather shellfish from their own reef, as it was so badly polluted. Thus, the tribunal claim “seemed a relevant thing to be involved with”.

Dr Gray is also part of a generation that graduated without debt. “I saw myself as having a responsibility to the community that trained me.”

He was to be a GP in Waitara from 1985 to 1992.

“I lived a stone's throw from the marae, which was a stone's throw from my clinic, and I became embedded in the town, really, particularly among the Māori community from the time I was spending on the marae.”

In Waitara, many Māori had a reasonable income and lifestyle thanks to the then freezing works (closed in 1995). At the time, most whānau kept gardens and had a lot of community support.

“It was fun being part of a town that had this Māori identity, which it had retained, despite the Land Wars and all the history behind that,” Dr Gray says. “Waitara was very cohesive around the marae.”

He says he was also lucky in his three GP partners at Waitara Medical Centre, all excellent GPs and very accepting of their hippie-activist partner.

“At my wedding, one of the partners made an ironic comment 'and then Ben found socks',” he recalls with a laugh.

Ben did find socks, but didn't give up activism. He got himself elected to the Taranaki Regional Council.

Life got in the way, though, after he and senior public servant wife Lynne Dovey had their first child. Dr Gray struggled to be a GP, local body politician, father and partner.

When their daughter was six months old, they moved to Wellington, where Lynne had career opportunities and other members of Dr Gray's family were living. He became main caregiver, house husband and home renovator, but it lasted only three months before he started to go “quietly mad”.

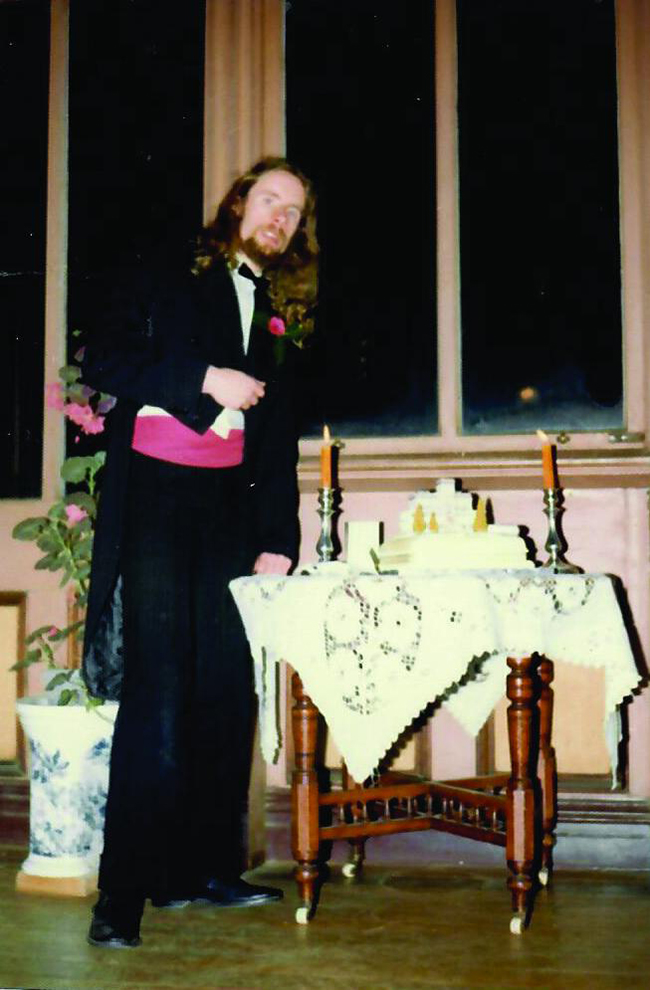

Long-haired Ben Gray at his 21st birthday celebration.

So began GP life at Newtown Union, among former classmates and friends, including Don Matheson, Julia Carr and Kathy James. They were kindred spirits. The leading-edge Newtown service had been founded in the late 1980s with a mission to provide affordable, accessible, high-quality care for those who usually fall through the cracks.

Dr Gray's clientele was no longer mostly Māori and rural. He says those Waitara patients were far more resourceful and resilient than the average city person. Now, he saw many patients who had enduring mental health problems and/or were refugees.

“It was my medical home,” he says.

In the early days he had to be “knocked into shape” by founding nurse Gill Regan; Newtown was a leader in interprofessional practice and team care.

The provincial doctor also arrived in the capital with a bad case of imposter syndrome.

He has since discovered this is not unusual among GPs and registrars.

What helped him get over his “just a GP” diffidence was coming across the literature around complexity, and understanding the skills of GPs differed from those of hospital specialists (“or 'partialists', as I like to call them”).

Different did not mean lesser. Generalist doctors have their own specialist skill set: “Once I understood that, I gained my mojo, if you like.”

Sharing his mojo with the next generation began when Dr Gray became a GP trainer, soon also convening conferences for the RNZCGP on complexity and professional practice.

In the early 2000s, the family spent a year in Boston, where his wife undertook an MBA at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and he volunteered during school hours at Boston University's new family medicine department. He taught consultation.

“I really enjoyed it, and discovered I had an ability,” says Dr Gray. “Here I was, at one of the biggest universities in the States, and they thought I had something to contribute.”

Bolstered by this experience, he took on part-time lecturing in his current department, then was appointed to a half-time senior lecturer role in 2006.

He continued as GP and lecturer, completing his masters in bioethics and health law along the way, until his retirement from Newtown late last year.

Of the practice life he has left behind, he says he will miss people the most.

“I'm used to meeting many people and being privileged to see into the details of their complex lives.

“I won't miss the ever-increasing accretion of bureaucracy, regulations, rules and ways of claiming funding…and all of that stuff, which has changed enormously during my time in practice.”

But he believes general practice is the way of the future. Secondary specialists, he reckons, are becoming too reliant on “expensive toys”.

Not only that, today's health concerns – with the exception of the COVID-19 pandemic – are dominated by long-term conditions. “And that [management and care] can only really be done in the community.”

Dr Gray says work needs to be done to develop the wider interprofessional primary care team, but the idea of the solo GP is well and truly out of date.

He regrets never getting evidence to support Newtown's own interprofessional model for antenatal care before it had to be abandoned for lack of funding.

One of the career contributions he is proudest of is the impact of his research and advocacy where professional interpreting in the consultation is concerned.

This includes getting Medical Council support for a chapter in Cole's Medical Practice in New Zealand on working with an interpreter.

His critique of the GP college's Cornerstone standards led to the requirement that patient notes state whether a patient needs an interpreter and, if so, in what language.

Research is part of every doctor's job, he says. “The job of a doctor has to be a combination of providing care, doing research about how you provide that care, and teaching the next generation.”

As the Medical Council pushes to have graduates spend more time in general practices, these need to become training institutions, he says.

Teaching and ongoing learning have played a key role in his “amazing career, both good and bad” at Newtown Union Health Service.

“I suspect that I have diagnosed far more cases of tuberculosis than many other GPs in Wellington. I've cared for more people who have committed murder… It's difficult, but learning how to do it means you learn an awful lot.”

Dr Gray is retiring as a GP who is now more than comfortable in his shoes…and socks.

This article is republished with permission from New Zealand Doctor / Rata Aotearoa.Find an Otago Expert

Use our Media Expertise Database to find an Otago researcher for media comment.