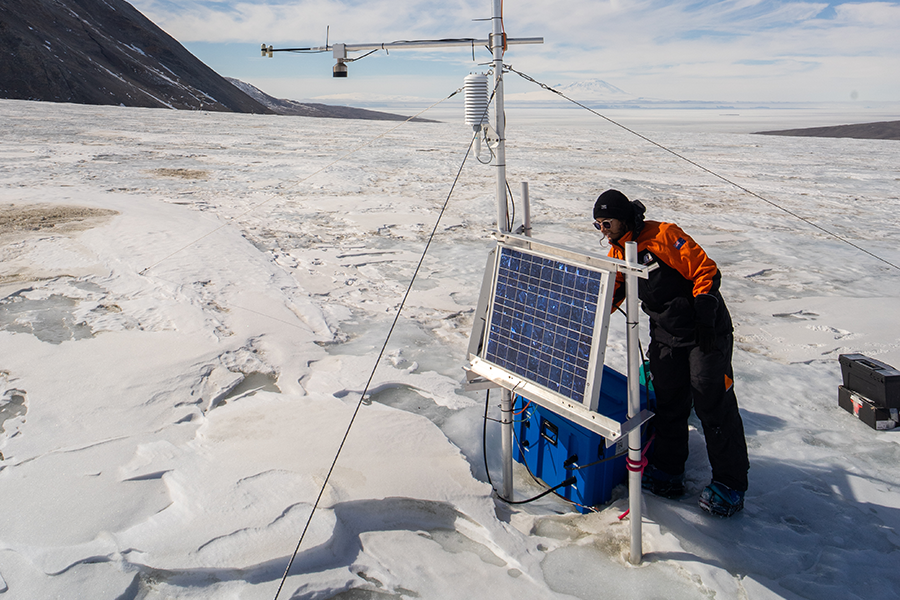

PhD candidate Tamara Pletzer is enjoying the challenges that come with conducting research in Antarctica. Photo: Marte Hofsteenge.

Adapting a hydrometeorological modelling system to track changes in glacier melt and stream flow in Antarctica has been a worthwhile challenge for one Otago PhD candidate.

Tamara Pletzer, of the School of Geography, hopes her research will help microbial ecologists determine which species stand a chance of surviving the effects of climate change.

“There’s a very fragile and unique ecosystem that exists in the Dry Valleys,” Pletzer says.

“It’s mainly cyanobacteria – so it’s microbial – but this ecosystem is really dependent on freshwater availability.”

There’s very little precipitation in the Dry Valleys, and all snow fall tends to sublimate rather than melt because the area is so dry and windy, she says.

This means almost all the freshwater available in the valleys comes from glacier melt.

Pletzer’s research has tested the capabilities of the model she has been using to carry out her research with. Up until her project began, the model had been used as the national water model in the United States and had been used in every continent-except Antarctica.

Fortuitously, not long before Pletzer started her project, a researcher in Colorado had coupled the hydrometeorological model with a snowpack model to model changes in mass balance on a glacier in Norway.

“I picked up that model but realised there would need to be a lot of changes made to adapt it to this extreme environment.

“We’re really pushing it beyond what it’s been used for in the past, every single component is being stretched.”

To make matters even trickier, the glaciers she works with are “really, really cold and extremely sensitive” and they melt for just a short period over summer and within this short period the melt shuts off due to refreezing.

Pletzer says visiting the freshwater streams in the Dry Valleys in person has really helped her to make sense of some of the information she is collecting via the models. Photo: Ian Hawes

These sporadic melt events crucially provide freshwater to the streams and enable the survival of the microbes, so accurately modelling glacial melt is both difficult, but important.

Pletzer realised there were a number of changes which need to be made to the model, initially testing it out at a point on Commonwealth Glacier to determine what needed to be modified and then implementing those changes.

That process took “quite a long time”, she says, but she is now at the phase where she has the model functioning. She can now model several valleys instead of just one point on a glacier.

It’s been “quite challenging” she says, but she’s also learned a lot from it.

“It’s really pushed what I know about models and development. It’s been a really fun process and I think there’s a lot of potential for the model now that it’s working.”

While previous researchers have modelled melt and compared it to observed stream flow, Pletzer’s project is explicitly modelling the stream channels in addition to glacial melt, which is helping to expand understanding of how these processes are linked.

The McMurdo Dry Valleys Long Term Ecological Research Project has installed a number of automatic weather stations in the Dry Valleys, as well as a network of stream gauges which provide a lot of the information Pletzer requires to test the performance of the model.

“We do not have measurements of the amount of melt generated on the glacier so stream flow measurements provide some of the best data for when there is melt.

However, not all of the melt on the glacier makes it to the stream gauge, so the data must be interpreted carefully. For example, it can evaporate or a lot is absorbed in the ground.”

“So that’s kind of the tricky part – working around sparse observations.”

It’s an issue many Antarctic researchers struggle with, she says.

Pletzer hopes to continue carrying out research on Antarctica once she finishes her PhD. Photo: Marte Hofsteenge.

Pletzer has visited Antarctica twice, once for five weeks during the 2021 – 2022 season, and again for 2 weeks during the 2022 – 2023 season.

During her first trip she visited a number of locations, walking around out in the Dry Valleys and collecting water samples from different lakes and ponds. She also flew a grid with an infrared camera mounted on a helicopter to collect high resolution land surface temperature and deployed a network of soil sensors.

“It was really good for me because I got to see a lot of the streams and glaciers in person. I think that really helps me when I’m looking at my models to see if anything makes sense or figure out where my model is going wrong.”

Her second visit saw her picking up soil sensors and installing instruments on a weather station.

When arriving in the valleys for the first time, via Scott Base in a helicopter, she was surprised by how steep the Dry Valleys were.

“My first impression was ‘woah these valleys are a lot deeper than I realised’ which sounds really silly, but I look at them from satellite imagery a lot, and you just don’t realise how steep the walls are.”

“It’s quite beautiful, you’ve got all this bare ground and then these really big glaciers that flow in, and they end in these really steep 20 metre cliffs, it’s quite impressive.”

It also struck her that there was no vegetation.

“It kind of looks similar to an alpine environment but without trees or tussock or any form of vegetation. It’s quite different and unique.”

Pletzer will finish her PhD project next year and would like to stick with Antarctic research in the future.

“It’s a unique region, I feel lucky to have a topic I really enjoy.”

-Kōrero by internal communications adviser, Koren Allpress