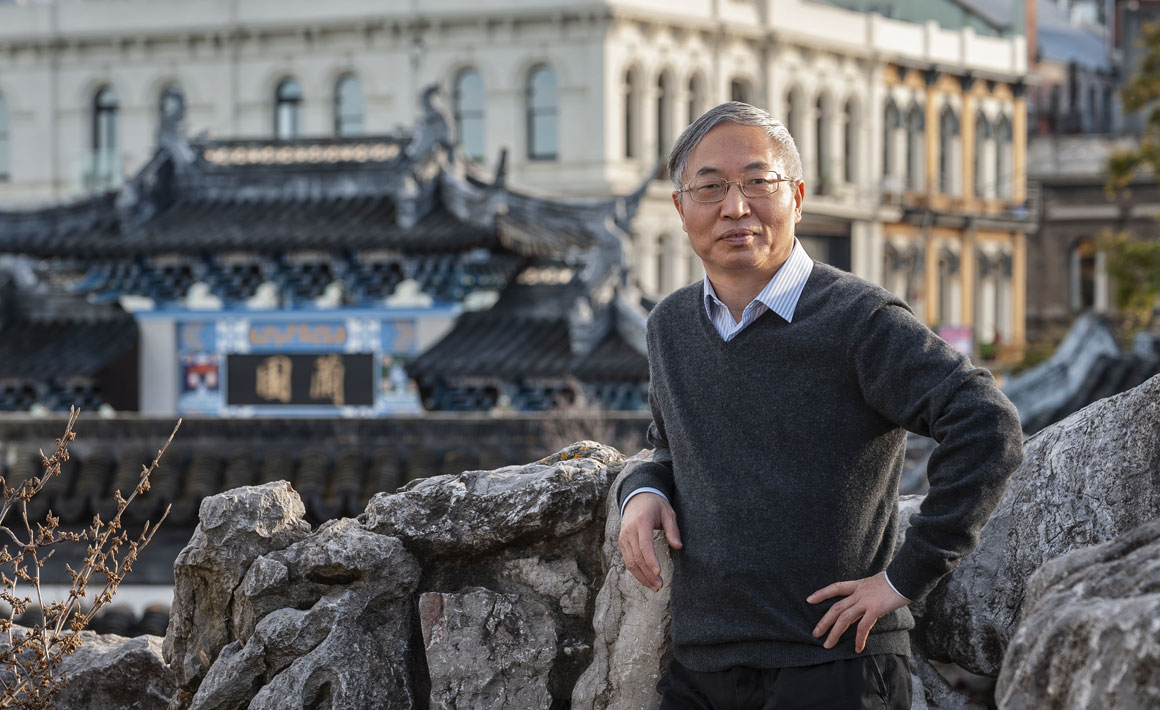

Professor Jing Bao-Nie: “How much can individual rights be undermined for the common good?”

Professor Jing Bao-Nie: “How much can individual rights be undermined for the common good?”The COVID-19 pandemic highlights important bioethical issues and shows just how destructive biological weapons could be.

How far is too far when it comes to ethical state responses to the COVID-19 pandemic? This is one of the questions posed by a University of Otago expert in bioethics.

Professor Jing-Bao Nie (Bioethics Centre) is researching the global bioethical implications of COVID-19, with a focus on China's response to the pandemic.

Nie says that the Chinese authoritarian model has resulted in significant advances in public health in China, including the apparently successful control of COVID-19, but has come at great cost to many individuals.

“Ethically speaking, there is a general issue in public health measures as to how much individual rights can be undermined for the common good. After all, good public health is for the well-being of the individual.”

Nie, who has extensively researched China's one-child policy, says that the Chinese response to COVID-19 has many parallels with the birth-control programme, which he describes as a draconian response to overpopulation and has inflicted massive suffering and state-directed violence on Chinese people, especially women.

He cites, as one example of China's authoritarian response to COVID-19, the colour-coding of every dwelling in green, red or yellow: people in red- and yellow-coded dwellings who broke the strict rules were punished.

“CCTV cameras have also been installed not just in residential areas, but even outside some individual apartments.”

He expresses related concerns over the silencing and humiliation of whistle-blowers who told the truth about the outbreak of the novel coronavirus in the initial epicentre of Wuhan.

Nie notes the difficulty in getting information out of China. “China now has a policy that, if scholars want to collaborate and publish internationally on the virus, they have to have permission. I feel very sad about this because China can offer so much to the global research about COVID-19.

“The international community needs a much stronger ban on biological weapons, much stronger protection against potential bioterrorism, and much stronger and transparent safety measures around scientific laboratories studying the most dangerous pathogens.”

“China is generally returning to Mao's totalitarian style of regime, one feature of which is that transparency and openness are not strong points.”

Authoritarian measures are not unique to China, Nie says, but countries such as Singapore tend to have “a softer authoritarian approach”.

He notes popular conspiracy theories in China that the United States intentionally brought the novel coronavirus to Wuhan, and theories in the West about the virus having been engineered as a biological weapon in a virology laboratory in Wuhan.

While he says the scientific evidence shows these claims are groundless, the devastating consequences of COVID-19 are nevertheless another reminder of the need for more effective global mechanisms to prevent biological warfare and bioterrorism.

“The current pandemic should be a call to the global community to take biosafety and biosecurity far more seriously because, more than any other, this virus proves how destructive microbes could be. In this context, states or terrorism groups may be more tempted to access viruses as super-weapons of destruction.

“The international community needs a much stronger ban on biological weapons, much stronger protection against potential bioterrorism, and much stronger and transparent safety measures around scientific laboratories studying the most dangerous pathogens.”

Nie is also researching the use of militaristic language and war metaphors in relation to the pandemic, something he has previously studied in relation to HIV.

He says that the ubiquitous use of such metaphors on a global scale – which is particularly strong in China – has unintended consequences.

“The use of military language undermines individual welfare and human rights and makes draconian wartime measures seem justifiable. It is also ironic, because one of medicine's primary goals has always been to heal and care, to save lives and to treat injuries caused by acts of collective violence.”

Nie is well-placed to exert outside scrutiny on China's response to the virus. He was born in China and trained there as a physician in Chinese medicine before studying sociology, medical humanities and bioethics in North America. He has closely collaborated with a number of scholars at several Chinese universities and has written extensively on medical ethics in China and global bioethics.

Funding

University of Otago