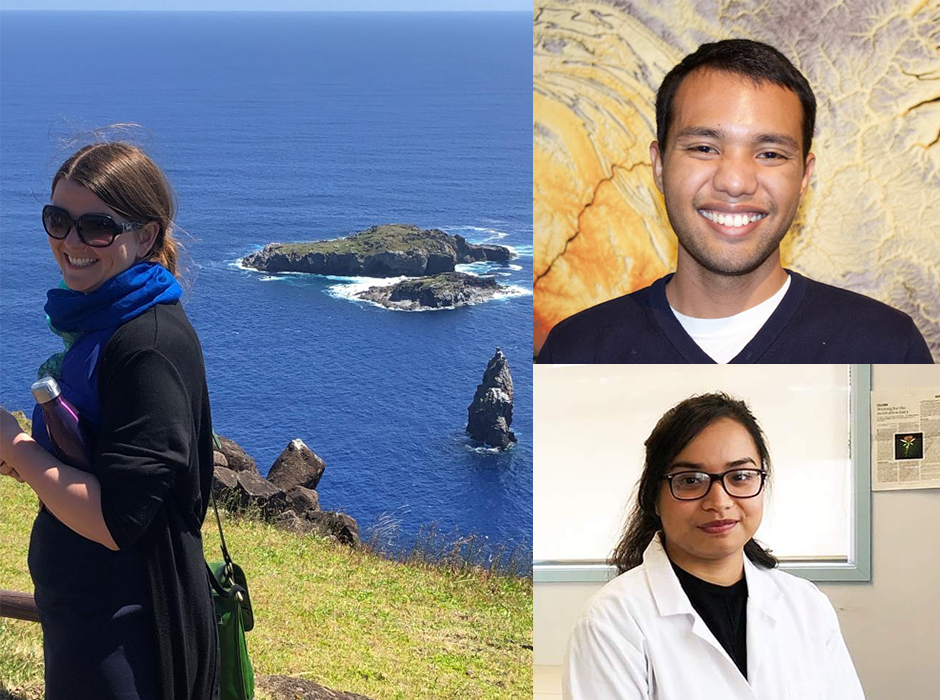

Clockwise from left Dr Anna Gosling from University of Otago’s Department of Anatomy, postgraduate researcher Tristan Paulino from Guam and postgraduate researcher Bwenaua Biiri from Kiribati.

“Ehara taku toa i te toa takitahi engari he toa takitini - I come not with my own strengths but bring with me the gifts, talents and strengths of my family, tribe and ancestors.”

Dr Anna Gosling shares this whakataukī to illustrate her research on how certain genetic traits of Māori and Pacific peoples - often perceived as vices in the modern world - could actually be virtues they adapted for based on their historic world.

“Though often interpreted figuratively, I believe this proverb can be considered quite literally in the context of genetics and how, over time, our ancestors’ adaptions can be passed down to become our own,” Dr Gosling says.

“This rings true in the context of our research, as we hypothesise that Māori/Pacific populations suffer disproportionately high rates of metabolic diseases, including gout and type 2 diabetes, because of an immune response they might have developed to fight against malaria.”

Based in the University of Otago’s Department of Anatomy, Dr Gosling is undertaking the Marsden-funded research alongside Professor Lisa Matisoo-Smith, Professor Tony Merriman, and postgraduate researchers Tristan Paulino, from the University of Guam, and Bwenaua Biiri, from the Kiribati community.

Dr Gosling says high serum urate levels are common throughout the Pacific, contributing to the higher-than-average burden of gout among Pacific peoples, but it also plays a critical role in the immunological signalling processes at the beginning of an immune response against malaria infection.

This means that Pacific peoples might have adapted for elevated serum urate levels over time to help fight against the malaria pathogen and increase their chances of survival.

“There is much stigma surrounding metabolic disease, so understanding how ancestors might have adapted these genetic qualities to overcome the challenges they faced is a valuable tool in understanding why this predisposition exists,” Dr Gosling says.

“Understanding how this works means we can help remove some of this whakamā surrounding metabolic disease and contribute to better health outcomes with more Māori and Pacific seeking treatment.”

Miss Biiri adds that a large part of her motivation to be a part of this research is that there have been few studies into how the genetic make-up of Kiribati people has affected their metabolic health.

She says research like this is important because it contributes to a greater understanding of metabolic diseases and hopefully will result in better health outcomes for the Kiribati population.

Similarly, Mr Paulino hopes this project will help reveal the context behind the presence of cardiometabolic genetic variation among Micronesian communities, so researchers can develop better intervention and management strategies for the diseases that might arise from this.

As an indigenous CHamoru researcher from the Marianas and Micronesia, he completed his undergraduate studies in Guam with his primary concern being how he could make a positive impact to help better his community.

Kōrero by the Division of Health Sciences Communications Adviser, Kelsey Schutte.