Associate Professor Dorothy Oorschot is a neuroscientist who researches the anatomy and function of the developing and adult brain. A particular area of interest for her is the impact of early life damage on the number of neurons in certain areas of the brain. In order to examine the functional impact of damage to these areas her team also looks at healthy brains. By comparing the healthy brain to the injured brain she is able to determine what is damaged, where, and what impact that damage is likely to have on the affected individual. While she and her team have examined a number of brain disorders over the years the main form of damage they focus on is hypoxia, also known as oxygen deprivation.

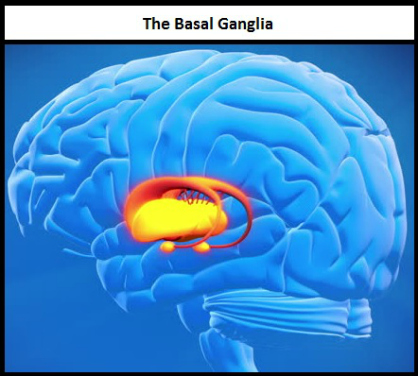

Hypoxia occurs when the cells in your body don't have enough oxygen. This puts your cells under stress and after enough time will cause them to die. Different cells will die at different rates, and Assoc. Prof. Oorschot and her team look specifically at the cells which die in a part of the brain called the basal ganglia.

Hypoxia occurs when the cells in your body don't have enough oxygen. This puts your cells under stress and after enough time will cause them to die. Different cells will die at different rates, and Assoc. Prof. Oorschot and her team look specifically at the cells which die in a part of the brain called the basal ganglia.

The basal ganglia is a processing hub for a number of different functions, but can be separated into two main sections: the ventral stream and the dorsal stream. The ventral stream processes some emotional and memory information, while the dorsal stream deals with motor information.

Initially, Assoc. Prof. Oorschot and her team examined the impact of hypoxia at a time that equated to birth after a full-term pregnancy. They found that when an individual has birth complications that result in them being deprived of oxygen prior to, during, or just after birth there is a high risk of damage to the dorsal stream of the basal ganglia. This damage results in cerebral palsy, which manifests as paralysis, muscle weakness, tremors, muscle stiffness, or any combination of those symptoms. Fifteen years ago there was no treatment for this kind of brain damage but, thanks to work done by researchers like Assoc. Prof. Oorschot, treatments have not only been developed but they are also constantly being improved. This work has been crucial in reducing the damage to the brains of these babies.

However hypoxia at full-term is no longer the most pressing issue in neonatal care. The focus is now turning toward extremely premature babies. Babies born extremely prematurely, between 22 and 28 weeks, now have a 90% survival rate. This is an incredible step forward in preserving life, but unfortunately there are costs. Between 50-70% of these babies may develop behavioural and memory deficits, both of which will impact their quality of life. Assoc. Prof. Oorschot believes that these deficits are due to damage caused by repeated oxygen deprivation. This oxygen deprivation, she believes, is resulting in injury to the ventral stream of the basal ganglia.

When a baby is born extremely prematurely not only are their lungs usually not well developed, but the part of their brain which controls their breathing is also not fully developed. As a result many of these babies will go into hypoxia multiple times a day. Their blood oxygen level is constantly monitored and once it falls below a certain level they are given more oxygen, but this is a very delicate balancing act. An increase in oxygen means an increase in free radicals, which can cause damage to the cells and DNA of these very premature babies. Damage can be done, and Assoc. Prof. Oorschot and her team are working on ways to minimize that damage.

After speaking with clinicians in the neonatal care unit of Dunedin hospital it became clear to Assoc. Prof. Oorschot that there were few viable treatment options for these babies. They needed treatments that used medications that were already available, at dosages which were known to be safe. This meant that any drug which hadn't been through clinical trials was off the table.

After speaking with clinicians in the neonatal care unit of Dunedin hospital it became clear to Assoc. Prof. Oorschot that there were few viable treatment options for these babies. They needed treatments that used medications that were already available, at dosages which were known to be safe. This meant that any drug which hadn't been through clinical trials was off the table.

Those kinds of restrictions can be very difficult in research, where newer is almost always seen as being better. She and her team had to look past drugs which could have been much more effective treatments because those drugs had yet to complete clinical trials. The choice was between developing a treatment which was potentially super effective but not available, or developing a treatment that worked well enough and could be used immediately. She chose the latter.

With that in mind Assoc. Prof. Oorschot and her team have been able to develop a treatment method, using the hormone melatonin, which looks to be able to prevent some of the damage caused by repeated hypoxia. It is not a perfect solution, but it is one of many steps toward improving the quality of these babies' lives.

“Extreme prematurity is an emerging crisis,” Assoc. Prof. Oorschot tells me, “The number of these babies who survive and will be affected is only going to increase as the developing world catches up to our medical standards.” In the US alone there are more than 80,000 extremely premature babies born each year, and there is incredible dedication shown by medical staff to ensure that these babies survive. Through her work Assoc. Prof. Oorschot has shown equal dedication to ensuring that the lives they live are of the same quality they would have had, had they been born 12 to 18 weeks later. We all want them to live, and she is working to make sure that they live well.

The success of work like this is due to an openness to collaboration. The collaborative efforts of Associate Professor Oorschot, her team, and neonatal physicians, have made this work viable. “When the data are all in,” she says, “I'll go across the road and present my findings to the local neonatal physicians, and publish it internationally.” And just like that, the lives of some of our most vulnerable children could be improved.

If you've enjoyed this article, or any of the other work we do here, please consider donating to the Brain Health Research Centre. Your generosity could make a world of difference.