The shoreline at Cape Evans.

Steve Broni’s journey from the slums of Glasgow to the sights of Ōtepoti – via Antarctica – may not have been all smooth sailing. But he is living his love of wild, empty places.

A book on Antarctic explorer Captain Robert Scott made a definite impression on Steve Broni when he was eight years old.

“I was fascinated with him and the Antarctic for a long time … my dream was always to go to there.

“I had a love of wild, empty places from a young age.”

But it was a dare, some courage and a bit of good luck which kick started Steve’s lifelong love of, and career in, very cold places.

Steve, the director of the University’s Science Academy, grew up in Glasgow. He graduated from university with a degree in marine science before winning a scholarship to do his masters in South Africa, studying African penguins.

“It wasn’t Antarctica, but it felt like a step in the right direction,” he says.

The day after Steve handed in his master’s thesis, he heard there was a British expedition called ‘In The Footsteps of Scott’ stopping over in Cape Town the next day enroute to Antarctica on board an ice strengthened North Sea fishing trawler the MV Southern Quest.

His friend dared him to go down to the dock and ask the captain if they needed any more crew.

So, he did.

The captain must have seen something in the young scientist, as he invited him back to for dinner that night. When he arrived, it seemed luck was on his side.

“I’ve chatted with the rest of the crew. If you want to join us we sail at 1pm tomorrow,” the captain offered to Steve.

“So that was me,” Steve says.

“I went back to my flat, told my girlfriend and packed a bag.”

Steve Broni, on the left, with Gareth Wood, heading off on a trip to Cape Royds.

The ship stopped in Aotearoa New Zealand, before making its way south. A small base hut was built at Cape Evans on Ross Island close to Scott’s hut and five men were left behind to winter over, three of whom would walk to the pole and be picked up by a light aircraft the following year.

Steve and the rest of the crew wintered over in Sydney before heading back to another part of Antarctica with a group of Australian explorers seeking to restore the hut of famous Australian explorer Sir Douglas Mawson.

The ship then headed to Tasmania to load the aircraft, a small Cessna 185, that would retrieve the three polar walkers from the South Pole in mid-January.

However, the smooth sailing was about to come to an abrupt end. The sea ice in the Ross Sea was especially thick that year and after unloading the aircraft the ship headed north out of the pack ice only to get trapped by two giant ice floes.

“The wind changed, and the ship became trapped; pinched by the two floes as they rotated.”

The ice punctured the engine room and the ship started sinking. All 25 of the crew managed to get off the boat with some supplies while the skipper radioed a mayday call.

“It happened really quickly, and there was a mixture of intense activity and fear as we unloaded inflatables and survival gear onto the ice. But everyone was safe.”

The American icebreaker Polar Star responded to their mayday call, and everyone was flown by helicopter to McMurdo Base, about 100km south.

The expedition had full insurance and could pay to fly everyone back to New Zealand. However, they would have to leave their base and the Cessna aircraft behind.

But, the expedition had made a commitment to not leave any visible signs of their expedition close to Scott’s historic Cape Evans hut, so determined to leave Antarctica as they found it one of the polar walkers, Gareth Wood, Steve and fellow crewman Tim Lovejoy volunteered to stay in Antarctica for another year until plans could be made to remove their base and the aircraft.

“For that second unplanned year we were basically Antarctica janitors, but very proud janitors. We had a point to prove about leaving the Antarctic the way we found it.”

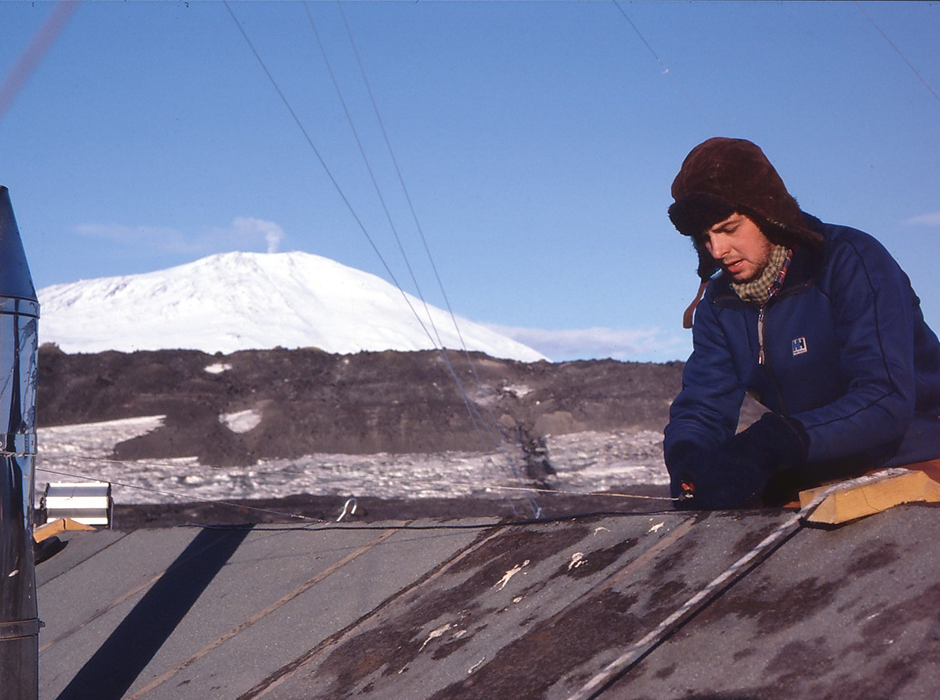

Steve Broni carrying out some maintenance work on the roof of the hut at Cape Evans.

At Cape Evans, they experienced about four months of complete darkness during winter, then during autumn and spring, they were treated to “the most beautiful pre-dawn light”.

The key to getting by in an Antarctic winter in a small hut was routine, he says.

They had plenty to do to keep the base running. Using a saw, they cut large blocks of snow which were dropped into two big empty drums inside the hut to melt for fresh water, the windmill and small diesel generator required maintenance, and Steve was involved in a project to measure the build-up of snow around Scott’s hut just 100m down the beach.

Another task that kept Steve busy was baking bread.

“Imagine you’re standing at the window, kneading the dough, and out there all you can see is wispy snow blowing over the sea ice, and far, far off are the Western Mountains and the light’s changing all the time.

“My bread used to be ‘kneaded to death’ Gareth used to say, because I’d stand there for ages.”

The trio would go on walks around the cape, or 10km up to Shackleton’s hut at Cape Royds, but safety was paramount. Katabatic winds and white-out conditions could spring up at any time. One area they didn’t expect danger from was the local wildlife.

“It was April, minus 35c. We were on our way back from Cape Royds, the sun was low and casting long shadows ahead of us as we walked. We were crossing some sea ice which had tidal cracks in it where the ice was a bit thinner. Next thing, a huge leopard seal suddenly broke up through the ice and grabbed Gareth just below his knee.”

He fell back on the ice, screaming.

“I just remember kicking this thing on the side of the head. It was like kicking concrete,” Steve recalls.

“I don’t know how many times I kicked it, until eventually it let go.”

Gareth shuffled back from the edge.

“I must have been in some kind of state of shock, because I remember standing there, looking down at the swirling water.”

Tim, who had been about 100 metres behind, finally caught up, yelling at Steve to get back from the hole.

And it was just as well he did, as the leopard seal shot back up again, this time with its full body up on the ice, and it grabbed the bottom of Gareth’s boot.

Steve went to his aid again, booting the attacking leopard seal until it eventually let go and went back in the water.

Tim and Steve examined his leg; there was no broken bones, but a lot of blood. They bandaged his leg as best they could and helped Gareth up.

“He set off at a cracking pace,” Steve recalls with a laugh.

Back at the hut they were able to get a hold of a doctor over the radio who gave advice on keeping the wound clean and changing the dressing until it healed.

Later, Steve wrote to the British Antarctic Survey, and they told him that while some of the men who accompanied Ernest Shackleton to Antarctica had encounters with leopard seals, Gareth’s incident may well have been the first completely unprovoked leopard seal attack recorded.

A sleeping leopard seal.

The trio’s stint as `Antarctica janitors’ came to an end in December 1986. A privately chartered twin-otter aircraft flew 4,400km across the Antarctic continent from Chile to retrieve them. Their base and Cessna aircraft was removed two months later by Greenpeace.

But Steve wasn’t ready for home, so he accompanied Robert Swan, Expedition Leader, on his lecture tour around the United Kingdom and Australia.

The Southern Quest had passed through Port Chalmers on its way south the year before and that was when Steve “fell in love with the Otago Peninsula” and so was keen to return to Ōtepoti.

The Footsteps Expedition had been granted work permits for Australia, but not Aotearoa, so he went back to Australia to work for the Australian Conservation Foundation’s Antarctic Campaign before landing a job at Otago Museum. He also travelled around the South Island giving talks at schools about Antarctic history, science and his own adventures before gaining residency in 1991.

The next 15 years were spent working for the Department of Conservation (DOC) in a variety of education roles.

“Being a lover of wild places, I would spend my holiday also working for DOC. I’d go down to Codfish Island (Whenua Hou) and help with Kakapo Programme or Stephens Island (Takapourewa) and help out there. It was the chance of a lifetime really.”

The most extreme was taking six months unpaid leave to help with Falkland Islands Conservation.

He has also worked coaching tour guides in Alaska and New Zealand, wildlife tour guiding on Otago Peninsula and a stint in Dunedin Public Library.

In 2009, while at the library, he was approached by Rose Harrison, who worked at the University of Otago. She asked him if he was interested in being involved in a proposed high school science academy.

“Rose said they were thinking of the area of greatest need – potentially high-achieving students from rural/provincial, small and lower decile schools.

“When she started saying that I identified strongly with the mission; I came from an east-end slum in Glasgow, and while I was deemed a potentially high achiever, I lacked opportunity to go to a good school.”

Steve with the Science Academy July 2015 students.

He helped set up the Science Academy in 2010, and 2011 saw the first intake of 52 students. Steve has now been Science Academy Director for 13 years and still looks forward to welcoming a new cohort of young minds every year.

He believes the earlier students are introduced to the concept of communicating science, the better.

More than 90 per cent of the 50 to 60 students who attend the academy go on to tertiary education, about half of whom enrol at Otago.

Steve is fond of the quote, “a ship in a harbour is safe, but that’s not what ships are made for”, and embraces the concept in his own work.

“Let’s just be brave, let’s get out there, take our science to the public, share our passion for it in an engaging way, and show them its relevance.”

- Kōrero by internal communications advisor, Koren Allpress