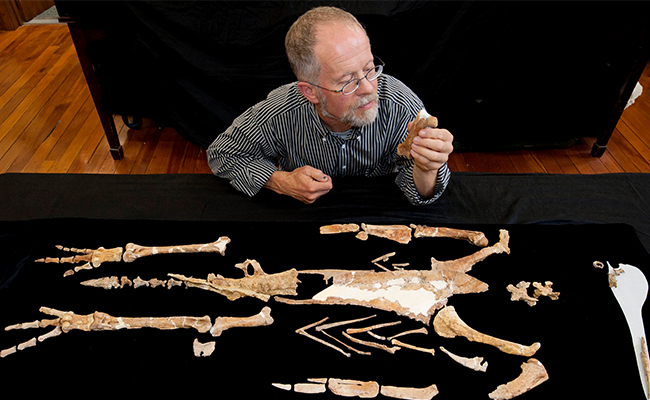

Professor Ewan Fordyce with a Kairuku, giant penguin fossil.

Professor Ewan Fordyce joined Otago's Department of Geology in 1982. Just shy of 40 years later he has called time on his teaching career.

Professor Ewan Fordyce was helping university students achieve their dreams even before he'd left high school. In the 1960s, a teenage Fordyce joined the Canterbury Museum's Junior Club where he met PhD students who needed to analyse fossils. With his ears pricking up at what they required, he took it on himself to assist them in their work.

“I was pretty fascinated by animals, fossil and modern, and I could see what they were doing, and what they were looking for. I thought, 'I can do this', so I went out on my own in weekends and collected specimens I knew they could use.”

In the subsequent 60-odd years a distinguished career flourished. Overseas stints at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C, and a postdoctoral fellowship in the Department of Earth Sciences Monash University in Melbourne, leading all the way to Otago.

Fordyce with McKay Award Hammer.

“I pulled up on my pushbike in 1982, walked into this office, and have been happily working here ever since. Deciding to retire was a hard decision, but I'm absolutely committed to it. I could see in the last couple of years that while I love my research and love teaching students, they need a fresh new face to stimulate them,” Fordyce says.

He will stay connected to the Department of Geology in a research capacity, having gained a Marsden Grant to investigate field sites for whales and dolphins from 18-20 million years ago. The work is on track for completion early next year.

Current Head of Department in Geology, Associate Professor Andrew Gorman, says Fordyce's contribution to Otago and the study of palaeontology in New Zealand has been immense.

“In addition to being an engaging lecturer, Ewan has a long history as a field geologist finding, excavating, and studying large fossil vertebrates from New Zealand's past. We also shouldn't forget his stint as HoD as well! During his time at Otago, he has trained many of New Zealand's palaeontology researchers and his expertise is drawn on from around the world,” Associate Professor Gorman says.

Professor Ewan Fordyce's Inaugural Professorial Lecture photo with Waipatia skull (fossil dolphin).

The Department of Geology has a proud record of long-serving staff, some tipping over 50 years. Fordyce puts the magnetism to the place down to the people within it.

“It's a great Department and has been for some generations. We have a sort of glue which holds us all together, we get on with each other and get on with our teaching and research.”

“I didn't really have much of a clue what I was doing, but I tried hard, and without anyone there to show me how to do it just had to discover things myself.”

Through the course of his career there have been some big accolades - winning the Royal Society's Hutton Medal in 2012 being a key moment. Along with the awards there have been standout scientific discoveries and adventures - one of the biggest coming thanks to a whiteout in Antarctica in 1987. There to assist a United States team searching for fossil whales, Fordyce was making his way back to base camp when he found himself caught in a whiteout. Pressing on in low visibility, he was looking down at the ground around his feet and noticed something protruding from the rocky surface.

“I thought, 'Hey, there's a bone on the ground,' I scraped around and found a few more. They were whale bones, and I picked one up and it had huge monstrous teeth protruding from it.”

Realising he'd found something new and different, Fordyce collected the bones from the site, and prepared them for display in the Smithsonian Natural History Museum, Washington DC. The fossil whale, now named Llanocetus, is a major piece in the evolutionary jigsaw of early whales.

Another big discovery was that of a fossilised giant penguin he found in a riverbed in South Canterbury. While working on his PhD in Christchurch, Fordyce used to travel outside the city to explore for fossils.

“I didn't really have much of a clue what I was doing, but I tried hard, and without anyone there to show me how to do it just had to discover things myself.”

Walking around an outcrop of huge fallen rock slabs Fordyce noticed an oval section of brown material protruding from the sandy limestone. What looked like a small piece of bone turned out to be exactly that.

“I chipped away and thought this is definitely part of a specimen, and it was showing signs of being much bigger.”

Professor Ewan Fordyce and the 34 million-year-old whale fossil he discovered from Antarctica.

As time was against him that afternoon, and in a serious test of patience versus haste, Fordyce had to leave the bone in place or risk damaging whatever else lay alongside it.

The days turned into weeks, months and years as Fordyce completed his PhD then headed overseas. It was 5 years before he got back to that riverbed and discovered the skeleton was of a giant penguin, around 1.3 metres tall. Fordyce and his collaborators named this penguin Kairuku, the diver that returns with food. The Penguin skeleton is displayed in the University's Geology Museum.

“I never thought I'd end up working on penguins, but that first big specimen was a real trigger for me.”

Ewan Fordyce's selfie on the MV Ushuaia at Browns Station Antarctic Peninsula.

While his reflections on his teaching career are fond, there is a touch of hesitancy about the future of geology given changing perceptions towards altering the landscape.

“Many people find that the idea of digging up Earth's resources to be distasteful. But show me a person who does not have a cell phone constructed with geological materials. We are all culpable. I think the most important thing if you are interested in ecology of the earth, you realise quickly that you are you are part of the problem.

“But it's not hopeless. Look at electric cars – they're really important, and they require some resources from Earth. They're not the only answer but they're going to help a great deal and maintain society,” Fordyce adds.

When the Marsden research is complete next year, Fordyce's official time at Otago will come to an end, but he says he'll always keep an eye on the Department of Geology and how his students' careers progress. No surprises where he plans to spend much of his free time as possible – in the outdoors examining the natural world.