Big

dreams

Otago alumnus Scott Gilmour is an inspiring man. He has forged a successful career and is now committed to helping New Zealand's less fortunate young people on their own paths to success. His I have a Dream project works to find long-term solutions to create generational change.

Many school students know their teachers, parents and peers expect that post-secondary studies will be part of their education. Many less privileged pupils are not so lucky.

Some don't even expect to finish schooling before heading off ill-equipped for the world they are about to enter. Without a good education, learned skills or even hope, their future could be bleak.

Scott Gilmour is working on changing that, promoting the dream of a better future to disadvantaged youth.

“If you can inspire and support kids during schooling through to employment or further study, you have a good chance of providing positive outcomes for them, their whānau and the communities they live in.”

The project he founded in New Zealand, I have a Dream, works with Kiwi kids from ages five to 20, supporting them to find a path to success – not just academically, but for life.

From small localised beginnings 17 years ago, it has grown into a promising project that inspires and empowers kids to dream and to achieve. It is rapidly accumulating success stories that highlight its effectiveness.

For Invercargill-raised Gilmour, whose own road to success included an Otago BCom in Management and Marketing, I have a Dream has high aims.

“We're looking at long-term solutions to create generational change. If you can inspire and support kids during schooling through to employment or further study, you have a good chance of providing positive outcomes for them, their whānau and the communities they live in.”

I have a Dream is currently a privately-funded charity. Gilmour wants to prove its long-term worth to government. “We've had contact with MPs from all parties. We really need cross-party support as there's not enough philanthropy to roll out what we're doing nationwide.

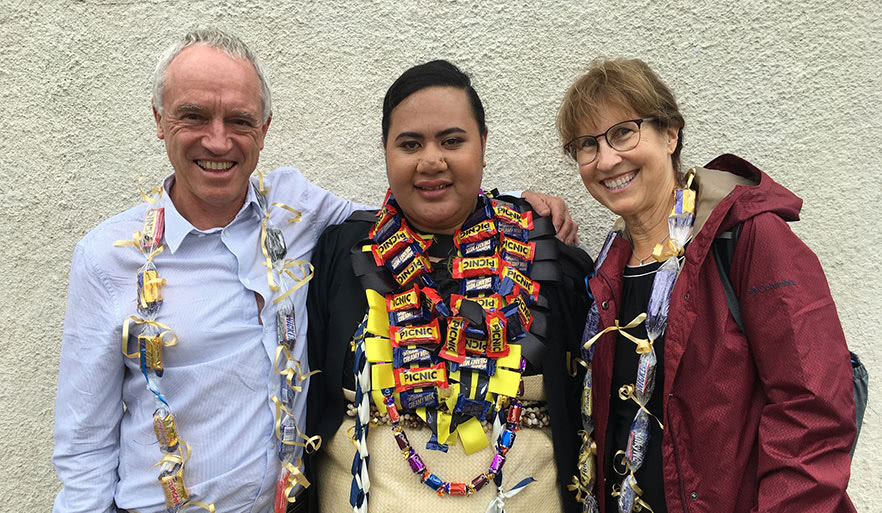

Scott and Mary Gilmour with Dreamer Salote Makasini who graduated from the University of Otago with a BSc in neuroscience in December 2018.

“Restructuring government social service delivery could do this at no extra cost to them. Our results show a 20 to 1 return on investment when you consider such things as lifetime earnings and taxes paid. But governments are naturally risk-averse and tend to think in the short term. Whereas social change is generational change.

“Our next steps are putting together a national business plan, looking for more partners such as iwi, and we might need another five years to get sufficient data to convince government of the effectiveness of our proposals.”

Gilmour is ideally placed to pitch the idea to politicians, bureaucrats, businesses and communities. His career has seen him in sales and start-ups, and he is still an angel investor, funding and supporting innovative start-up companies.

He never had a long-term life plan, believing that if you don't plan ahead it frees you to take new directions when doors open. While he appreciates his upbringing was comfortable, since then he has made his own way and has certainly made the best of opportunities.

Choosing a degree was not so much a passion for business as eliminating subjects he didn't like. But he found inspiration in his second year when he started using computers for analysis, agreeing with his father's advice that they could well be the future.

Graduating with a double major, Gilmour landed a sales position with Burroughs in Christchurch, where he discovered how businesses actually worked and how computers could be used effectively.

Life took an unexpected turn when he met an American girl tramping in New Zealand. “We knew almost instantly that we were going to get married.” A year later, when Gilmour was ready for a traditional OE, the couple passed on Europe and headed to the States instead. In six months they toured 20,000 miles together in a small car. “If you can survive that, you can survive anything.”

They settled in Portland, Oregon, with the idea of starting a family and heading back to New Zealand after a few years. Gilmour joined NCR in sales, but soon felt he needed to move on from selling. With few options available at the time, he decided to advance his education with an Executive MBA.

“NCR were very good and funded my first year, where I was able to work and study side by side, but I couldn't see a future with them so left and self-funded my second year.”

Gilmour took to mature study with a passion, working with real-life situations. “I had to do a full-year business plan using activity-based costing theories. At last accounting made sense.” So did business. Gilmour and a fellow student used the study to start their own software company from scratch.

A group of Dreamers – and Navigators – cycled the Otago Rail Trail in 2019. For most it was their first trip to the South Island and the furthest they had travelled without whānau.

“We raised money to start it, but as I also had a mortgage and two kids and debt from study, I needed an income too so I joined Intel, which was a fantastic place to work, rather like doing an ongoing MBA.”

For eight years Gilmour ran parallel careers, working for Intel by day and working on the start-up on some nights and at weekends.

When the opportunity came to head Intel's operation in New Zealand, it was perfect. “We now had four kids and our five years in the States had expanded to 15. It was time.&rdquo.

During Gilmour's four years as general manager of Intel in Auckland, he had high visibility, with a broad experience in management, marketing, development and investment.

That visibility led to him teaming up with Andy Hamilton, of Icehouse, and others to co-found Ice Angels, a business network that invests in and supports promising teams exploring global opportunities.

“New Zealand desperately needs to figure out how to develop more businesses where we add value to what we do. We can't keep relying on industries such as forestry, agriculture and high-risk tourism.”

In 2019 Gilmour received the annual Arch Angel Award from his investment peers for his contributions over the years and, possibly, his sense of humour. “My first reaction was shock and then amusement. I reckon I got it just because of longevity as I'd been doing it for so long.”

Throughout his years in the States and in New Zealand, Gilmour remained involved in his own software company, which he had helped to nurture all the way from the first business plan and capital raising through hiring staff, strategic planning, expansion and, finally, to a successful sale of the company. It was another life-changing event.

“We'd made every classic mistake start-ups make, but in the end, after 13 years, we'd become an overnight success. I now had the resources to do something else.”

One of the first things he did after selling the company was to dig out an old newspaper clipping he had filed after it fired his imagination in the US.

The item reported the success of the I have a Dream project supporting disadvantaged kids through school. It had started in East Harlem in New York City in 1981 and had been running for about a decade when it came to Gilmour's notice.

Gilmour felt the model could be a perfect fit for New Zealand. He approached the American organisation for permission to set up the first similar project outside the US.

“I didn't know much about education or social work, but it looked like a great business plan to me. Then I found out there were more than 20,000 different charities in New Zealand. Did we really need another one.

“After six months of investigations and talking to lots of people doing great things for kids I found there was really nothing like I have a Dream.”

Gilmour emphasises two standout differences. “The first is inclusivity. Most aid programmes target the top 10 per cent of kids on the bell curve or the bottom 10 per cent. We target the whole cohort, including the largely overlooked 80 per cent in the middle. We aim to move the whole bell curve up. Working with kids from years one to 15 and beyond, we have shown that the whole group has potential for greater outcomes than they would have otherwise.

“The second difference is timeframe. Most programmes run for a few months or for one or two years and involve one activity. We run for 10 to 15 years and include everything: literacy, numeracy, soft social skills and all you need to get a job or go on to further study.”

Breaking out of generational issues and challenges such as the cycle of poverty involves youth getting support from a four-legged stool, says Gilmour.

“The legs are family, friends, culture and community, and education and employment. Take away any one of those four and it becomes harder. Take two away and it's harder still. Lose three and you are likely to get lost. This is where the gangs step in and provide alternative social structures.”

Gilmour has seen many participants in I have a Dream respond and blossom. Some have fallen by the wayside, but supporters are still standing by them and they still have opportunities to turn their lives around.

“The key to I have a Dream is the people who keep it going. I funded the first round and promote and support it, but the people who do the day-to-day work deserve all the credit for its success. We are also blessed with many generous donors to fund this expansion. Now can we find more people who can help us set it up around the country?”

Gilmour appreciates education – and Otago. “Lessons you pick up at Otago are foundational. You leave home and learn how to live independently and get on with others. You learn time management and meet different people from different places doing different things. You get to evaluate life and look at your choices.”

“University can be powerfully formative. Otago woke me up intellectually, socially and emotionally.”

Campus life in Dunedin gives graduates an edge, says Gilmour. “I and other business people I meet find Otago graduates typically shine out among job seekers coming from university.

“University can be powerfully formative. Otago woke me up intellectually, socially and emotionally.”

Otago has also inspired participants in I have a Dream. After an exploratory 2019 visit to campus, half of one group decided they wanted to study at Otago. And when one of the programme's early protégées crossed the stage to be capped in neuroscience, Gilmour felt as proud for her as he had for his own children who had graduated not long before.

I have a Dream is now working with over 800 kids in Whāngarei. Eventually Gilmour wants to see New Zealand roll out the programme to all high-needs communities in the country so their young people can get an opportunity to share in the same kind of experience.

Learn more at ihaveadream.org.nz

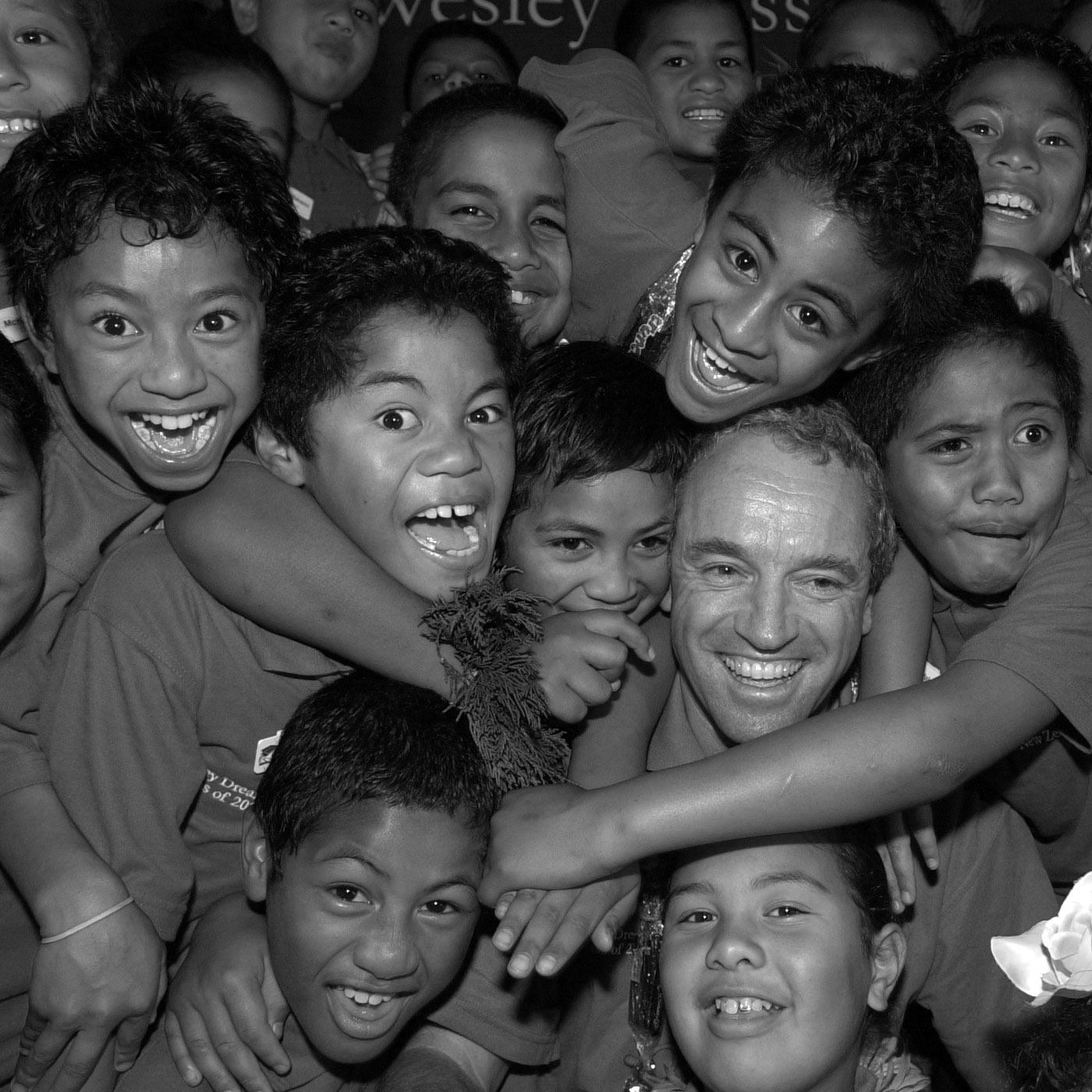

Scott Gilmour with young Mt Roskill Dreamers at the I have a Dream launch in 2003.NIGEL ZEGA