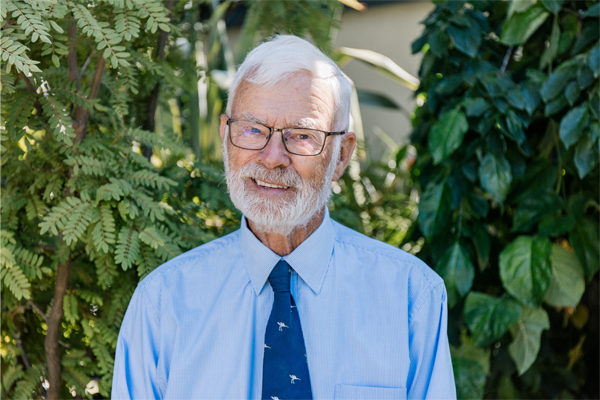

An extraordinary life journey has taken renowned conservationist and science educator John Darby from orphanages in the United Kingdom during war time, to Assistant Director of the Otago Museum, Honorary Lecturer in Zoology at the University of Otago and champion of the region's rare and vulnerable wildlife.

The Otago science alumnus was named an Officer of New Zealand Order of Merit (ONZM) for services to wildlife conservation and science in the 2023 New Year Honours list. John graduated from Otago with a BSc in 1981 and lives in Wānaka.

Sharing his reaction to receiving the honour, he says “nothing I have achieved in New Zealand has been done on my own. The successes, no matter what they are, have been made with the help and support of a huge number of Kiwis over a time of almost 7O years. Thus I feel that my successes are as much those of this country and its peoples as they are mine.

“I could never have imagined that the many awards I have received and especially the ONZM could have ever happened to the lonely and insecure orphan farm boy that arrived in this country so long ago. It is very humbling and I extend my gratitude to those who thought me worthy of such praise and made everything I have achieved possible.”

John took up the role of Zoologist at the Otago Museum in 1969 and was appointed Assistant Director in 1971. He developed many science-based holiday programmes for children and senior students, including setting up 'Discovery World' at the museum, New Zealand's first interactive science centre.

As a scientist, he spent two decades researching the conservation needs of the yellow-eyed penguins (Hoiho) on the mainland and New Zealand Sub-Antarctic. In 1985, he negotiated the purchase by the World Wildlife Fund of the largest breeding area of yellow-eyed penguins on the mainland, engineering the first fully-protected area for the species.

John was a foundation trustee of the Otago Natural History Trust and the Yellow-Eyed Penguin Trust, served on the board of the Otago Science into Action project, on the Scientific Advisory Group for the Otago Conservation Board, was former President and committee member of the Otago Institute, and member of Forest & Bird for more than 65 years.

He has spent the last 10 years on the conservation of the rare and threatened species of water bird, the Australasian crested Grebe (Puteketeke) in southern New Zealand. The Puteketeke project has been undertaken around Lake Wānaka, Lake Hayes, Lake Wakatipu and Lake Hāwea and John is assisting in the preparation of a management plan for the species.

In 2017, the Royal Society Te Apārangi made John a Companion of the Society (CRSNZ) in recognition of his work in science education.

He says in 1998 the Alumni office at Otago anticipated the ONZM, when they made a series of special awards to mark the Diamond Jubilee of the Graduates' Association.

“I was a recipient of one of those awards, specifically for contributions to science education and conservation. I was immensely proud of that and still am and treasure it greatly. I think it quite amazing that almost 25 years later, the honour from the State echoes that of the Alumni.”

An extraordinary journey from wartime orphan to wildlife authority

John arrived in New Zealand in 1954, “euphemistically known as a 'home boy'. It was a derogatory term used in the UK to describe boys who had lived in orphanages”.

From birth to when he left the system at 15, he had lived in eight different orphanages and one foster home, where he suffered a serious injury to his right eye.

“I can recall the time I was growing up to the sights and sounds of the war; the sound of aircraft, sirens, bombs and guns. The sight of searchlights (viewed by standing on my bed and peeping through the curtains during blackouts), and the claustrophobic effects of air raid shelters and fear of gas masks.”

After his 15th birthday he was placed on a dairy farm, which was “very much a cultural shock as well as a physical one”. It was on a property in Surrey that hand-milked pedigree Guernsey cows twice daily, up at 5am, rarely finished work by 6pm. It was exhausting, even more so during winter when cows were in stalls for nearly five months or more. I had one day a week off.”

John says one of his places of solace on the farm was a small copse, which he called Bluebell Wood. “At times during the day (we often had free time in the afternoon during summer), I would walk there, not far, and just sit and do all my thinking, and sometimes crying.

“As far back as I can remember, I did everything possible to try and find my mother and really hoped that being free of the strictures of orphanage life and working on a farm to earn money, that one day I would be able to find and hug her.”

When he was 16, the lady who owned and managed the farm, with support from the vicar of the local church, helped him succeed in his longtime quest to find his mother.

“She agreed to meet me at a railway station in London, but only on condition that I was not to try and find out where she lived. I guess I reacted badly, but I withdrew all my savings and went into town and bought a boat ticket to Australia.”

However, he needed a passport, someone to sponsor him, guarantee him a job and be his guardian until the age of 18. In the end, he came to New Zealand on his own when he was 17, as a farmhand sponsored by Lincoln Agricultural College. The Registrar, Gordon Hunt, was his Guardian.

“I will be forever grateful as to how they cared for me. Only one or two people were aware of my background and not to have to explain myself was quite wonderful. The shame I had lived with all my life until Lincoln was gradually shed.”

A week after arriving, he enrolled in Christchurch Polytechnic to undertake School Certificate.

“It was a wonderful experience in many ways. I would put my bike on the back of the bus to get into Christchurch and ride back to Lincoln after tech finished. In the summer I loved the ride over the Canterbury Plains with those stunning views to the Alps. But above all, I was judged by who I was rather than a derelict 'homeboy'.”

The following year, having moved to the North Island for a different farming experience, he contracted polio and spent seven months in Auckland Hospital and another three at Duncan Hospital in Whanganui.

After recovering, he returned to Lincoln to complete his Diploma in Agriculture, graduating in 1958. From there, he went to the then Ruakura Animal Research Station (now Ruakura Research Centre) in Hamilton to get up-to-date with the latest information and technology.

“Farming went out of the window shortly after I arrived at Ruakura, when I became aware of a search for a technician for the facial eczema research team. I was in science heaven, it was quite wonderful. Half my work was in the field and the other in the lab. The whole experience being part of a research team was astonishing.”

Deciding it was time to really challenge himself, John enrolled at the University of Canterbury (UC) to do a degree in Zoology.

“I tried Zoology, Botany, Chemistry and Physics all in my first year, and not surprisingly failed miserably. I managed to get a job in the Zoology department during the vacation and that morphed into being invited to join the department as a full-time staff member.”

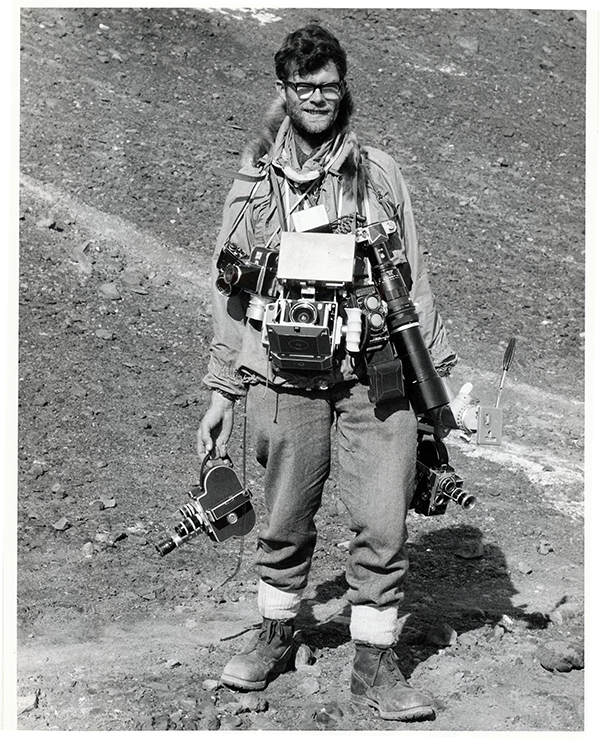

John Darby at Cape Bird, Antarctica, in 1966

He went on to work as a technician at UC for six years and took on the role of photographer. During this time, he spent three summers as deputy leader and leader of UC's Antarctic research unit, studying the

In 1969 he took up the position of Curator in Zoology and Head of Sciences at Otago Museum. He served as Assistant Director from 1971 until he retired in 1999 and was responsible for all natural history displays and the curation of the Zoology, Geology and Botanical Collections.

“The prime focus of the Museum was and always would be the care, maintenance and stories of the collections. Beyond that I had a vision of what, as an institution, we could we do for the community that no one else was doing.”

In 1971, John initiated the “Young Explorers Week” series of holiday programmes and Science workshops for senior students. The latter was a joint programme with assistance from staff at the University of Otago, and this eventually morphed into the University's Hands On Science programme.

“I recall discussions with Neville Peat on how unaware the public were of the richness and variety of wildlife in and around the city. Dunedin really was the wildlife capital of New Zealand, there seemed to be no reason why we should keep this a secret.”

Shortly after arriving in Dunedin, he was invited to join the Board of the Otago Peninsula Trust, and it was from that platform he assisted with getting the Royal Albatross Colony opened to the public, with the first public information displays created by the Museum.

The Museum also had a close association with the newly-formed TVNZ Natural History unit, acting as advisor to a number of their documentaries as well as the Macrocarpa Cottage and Wildtrack series'.

In 1979 John embarked on a long-term study of the yellow-eyed penguin and in 1993 was appointed an Honorary Lecturer in the Department Zoology, supporting many postgraduate studies on this species.

Most of John's penguin fieldwork was undertaken in southern coastal South Island, and he has tramped almost the whole of the coastline from Moeraki to the Catlins. He also worked on Auckland, Enderby, Campbell, Codfish and Stewart Islands and has published extensively on wildlife conservation subjects, particularly concerning yellow-eyed penguins.

Following an invitation as guest speaker to the Australian & New Zealand Association for the Advancement of Science (ANZASS) conference at Melbourne's Monash University in 1985, John was invited to present a paper on his work to the British Seabird Group at the University of Oxford.

“This invitation gave purpose to my first sabbatical leave and the opportunity to visit leading museums in the UK, USA and Europe, including six weeks in Denmark with a scholarship from the Danish Ministry of Cultural Affairs. Science museums were a high priority.”

During this time, among many discoveries, he at last managed to find his mother in an old folk's home in Leicester, England.

“The discovery and reunion created memories that will never be forgotten. Over the years, newly discovered members of my UK family were uncovered and many have visited New Zealand and joined in celebrations with my NZ family.”

Kōrero by Margie Clark, Communications Adviser Development and Alumni Relations Office